- Architect

Deborah Berke Partners - Location

Philadelphia - Completion Date

Fall 2021 - Terra-cotta

Shildan Group - Windows

Wausau Window & Wall Systems - Metal Panels

VMZINC ‘QUARTZ-ZINC’ - Facade Installer

EDA Contractors - Entry Doors

Kawneer - Waterproofing/Air Barrier

Henry Blueskin VP160

- Exterior Insulation

Rockwool Cavity Rock

With much of its campus shaped by eclectic historical architecture, the University of Pennsylvania sought an updated look for its new Meeting and Guesthouse. Serving as a space to host important dignitaries and other special events, the Meeting and Guesthouse by Deborah Berke Partners was built as an addition to two Victorian townhouses designed by Frisbey Jones. Adjacent to the President’s House, the Meeting and Guesthouse will also serve the need to host high-level meetings with university administration, and to allow ample space to host guests of the President.

Penn tasked Deborah Berke Partners with not simply mimicking the existing Victorian townhouses, or other historic campus architecture, as the university wanted the new building to meet high environmental standards, such as taking into account the building’s life cycle. Additionally, as the existing buildings sat significantly above grade, accessibility was critical.

The existing townhouses were in need of significant work, requiring masonry repair, and work on facade details “ranging from plaster, to sheet metal, to carved wood,” explained Deborah Berke Partners partner Stephan Brockman. Working with a request from the president’s office, the design team sought to update the building to be presentable for a contemporary audience rather than attempt to restore it exactly to its original state. This included landscaping, which provided additional privacy to guests, and new window glazing. Insulated glass units were installed without having to remove the original single-pane glass as the window sashes were amply deep, rendering the windows inoperable but increasing their performance. The load-bearing masonry walls were also kept—with one extended for a new egress—and bolstered by a steel frame with wood joists.

The addition rises four floors, with a ground floor terrace serving as the building’s new entryway and hosting the main public spaces, including a lobby and large multipurpose room. The second floor contains meeting rooms, the office of the president of the Board of Trustees, and additional office spaces, while the upper two floors are reserved for guest spaces. Floor-to-ceiling windows open the ground floor to the terrace, with sliding glass doors allowing the building to be opened to the terrace during events, “maintaining the circulation, but using architecture to make it a little bit more graceful,” said Brockman. Thermally broken aluminum windows on upper floors allow guests views of the terrace while providing ample privacy.

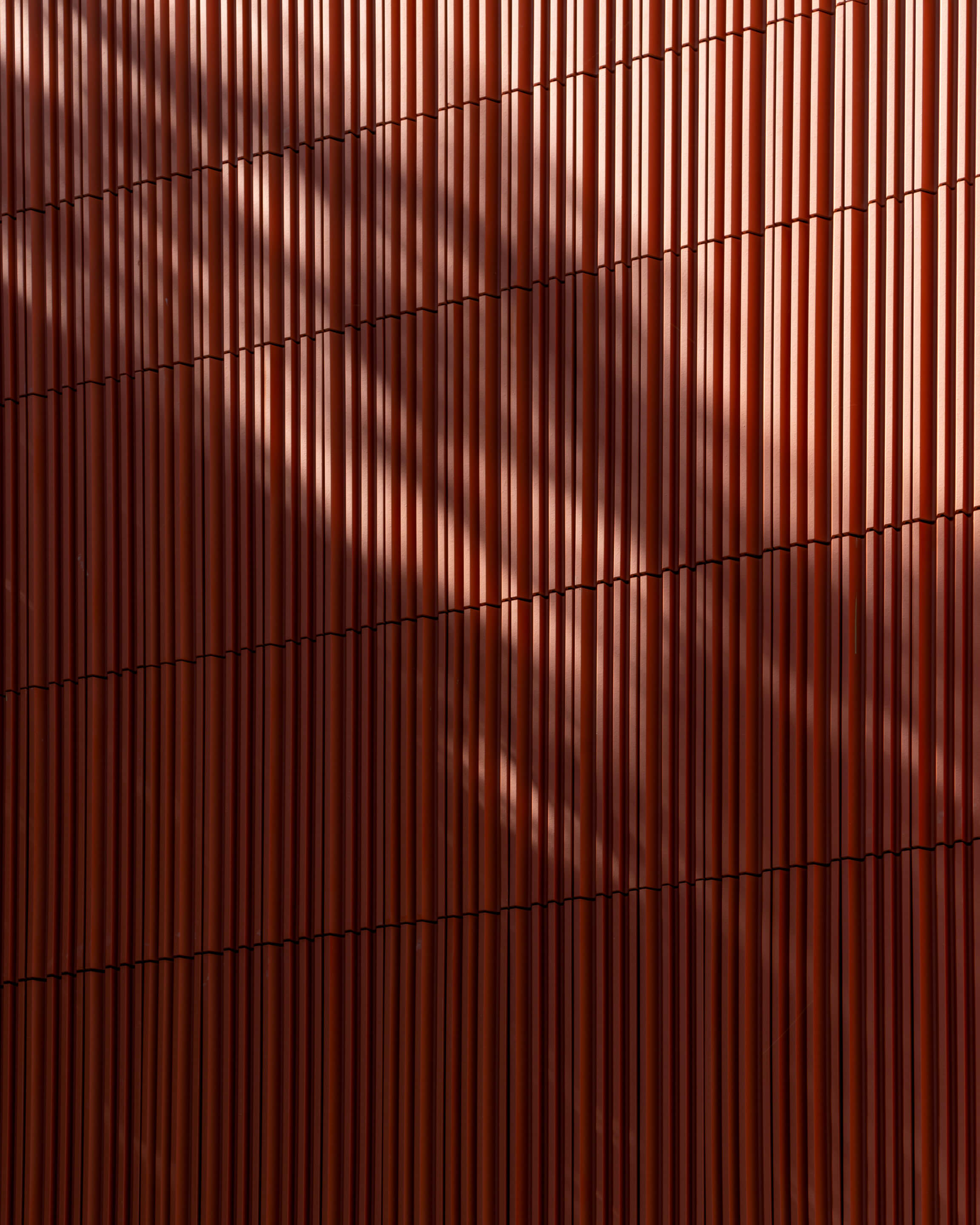

The building is wrapped in terra-cotta, which covers the entire facade save the windows and entryways. The effect is a geometrically consistent facade shaped by “baguettes” manufactured by Shildan, with a shape that makes the terra-cotta appear to be arrayed in long, thin strips rather than panels, with a color that reflects the brick of the townhouses without attempting to copy them. The townhouses contained two types of brick: Roman-sized iron spot brick and a more typical orange-red brick that is common throughout Philadelphia. Working with mock-ups in the parking lot next to the building, the design team was able to test how different colors of terra-cotta looked against the brick on the townhouses.

Given the existing brickwork on Penn’s campus, constructing another brick facade would have been like “bringing one too many bricks to the party,” said Brockman. Terra-cotta provided a solution in its “sense of masonry and solidity” without being brick. The design team paid close attention to how light played off of the terracotta, staying true to the early-stage concept of a light-veiled form that had been shaping the building’s design. The folding and rippling of the terra-cotta was augmented by its interaction with daylight, creating the veiling effect. This was also enabled by the choice of the baguette form over something more solid, both literally and figuratively, lightening the facade’s material. Brockman said that for a building of its size, there was an incredible range of potential material solutions, and emphasized the contrast between the terra-cotta rain screen of the addition and the weight-bearing masonry wall of the Victorian townhouses.