Revision and tweaking are central to the architectural process, but it is not often that a practitioner gets the chance to design the same project twice. When the Stuttgart, Germany–based firm Behnisch Architekten first won the commission for a new biomedical research facility at Harvard University, George W. Bush had just started his second presidential term and the university’s expansion into Allston, a Boston neighborhood just across the Charles River from Cambridge, had yet to concretize. The new research building would be its centerpiece.

With an already wide-ranging portfolio of institutional research facilities, which included Cambridge’s own Genzyme Center, the first building of its size to earn LEED Platinum certification, Behnisch originally conceived of the Allston project as a group of four discrete structures. But by early 2010, with foundations excavated and early construction underway, the ongoing global financial crisis forced the project onto the back burner. Behnisch helped seal the site’s new basement and waited for the call to return.

It took four years. When Harvard invited the firm back, administrators had already decided to reconfigure the project to house large portions of the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences faculty, renaming it the Science and Engineering Complex (SEC). The architects devised a new plan to integrate the often-divergent spatial needs of students, educators, and researchers under a single roof. “It didn’t look close to what we originally designed,” Stefan Behnisch, the firm’s founding partner, recalled.

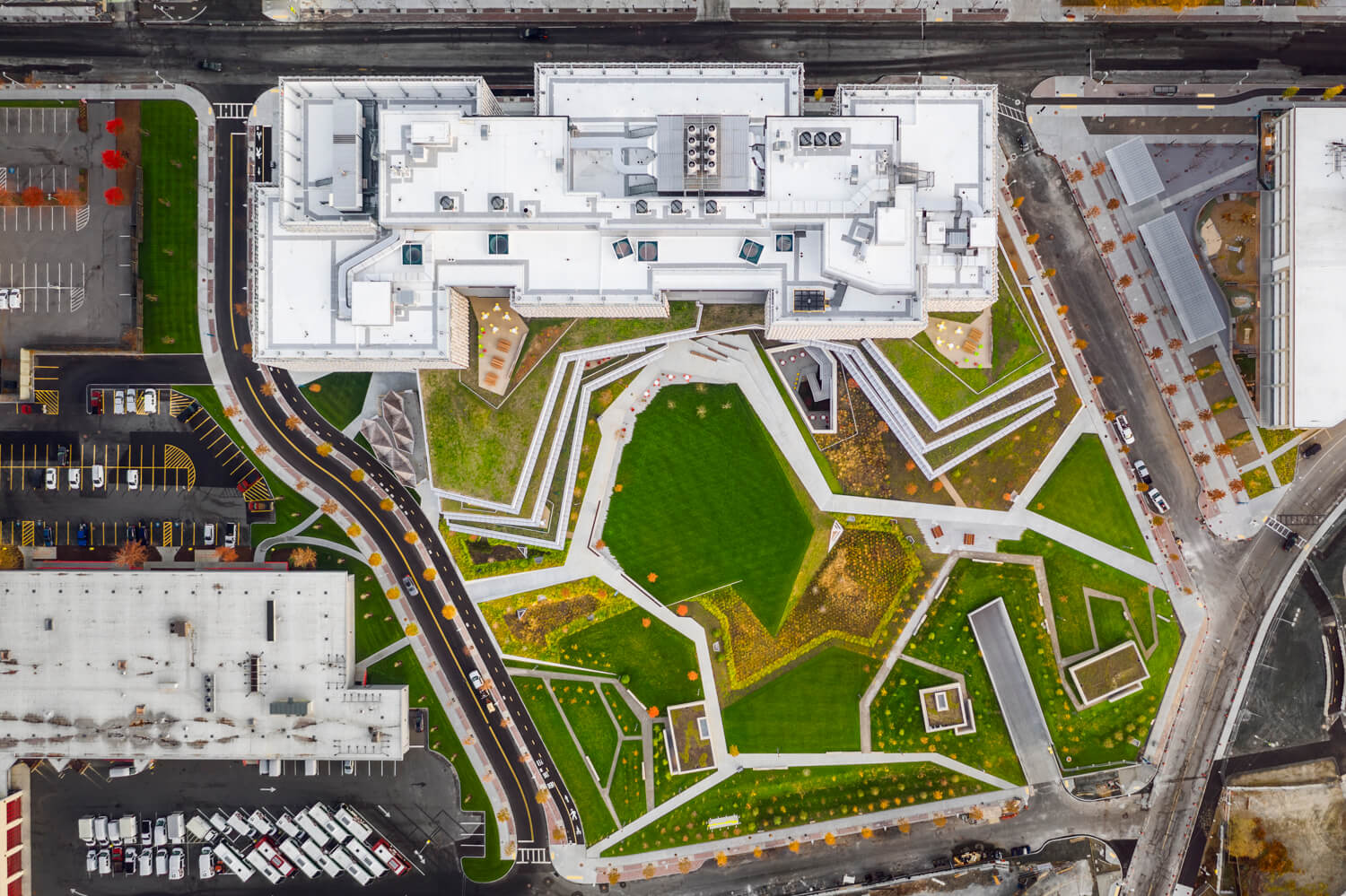

The result is a highly adaptable, LEED Platinum–certified facility with 544,000 square feet of classrooms, offices, laboratories, and lounges methodically divided among eight total floors, two of which are subterranean. “Research usually requires more stability than teaching spaces can provide,” project head Matt Noblett told AN, “so we concentrated student activities in the lower, more public levels of the building.” These stacked floor plates recede as they ascend, accommodating a central atrium and vegetation-filled terraces at the edges of the structure. Seven reconfigurable classrooms, four large-capacity lecture halls, makerspaces, and smaller seminar and meeting rooms are strategically interspersed within a matrix of open gathering spaces, facilitating social interaction among the building’s users.

The laboratories, by contrast, are housed in three outwardly distinct volumes that appear to float above the lower terraced floors, insulating them from the more dynamic and high-traffic parts of the program. The architects grouped wet labs in a single sector of the building to take advantage of the infrastructural and energy-related efficiencies that come with proximity. The interstices between volumes are again dedicated to communal lounge spaces that lend themselves to the occasional chance encounter.

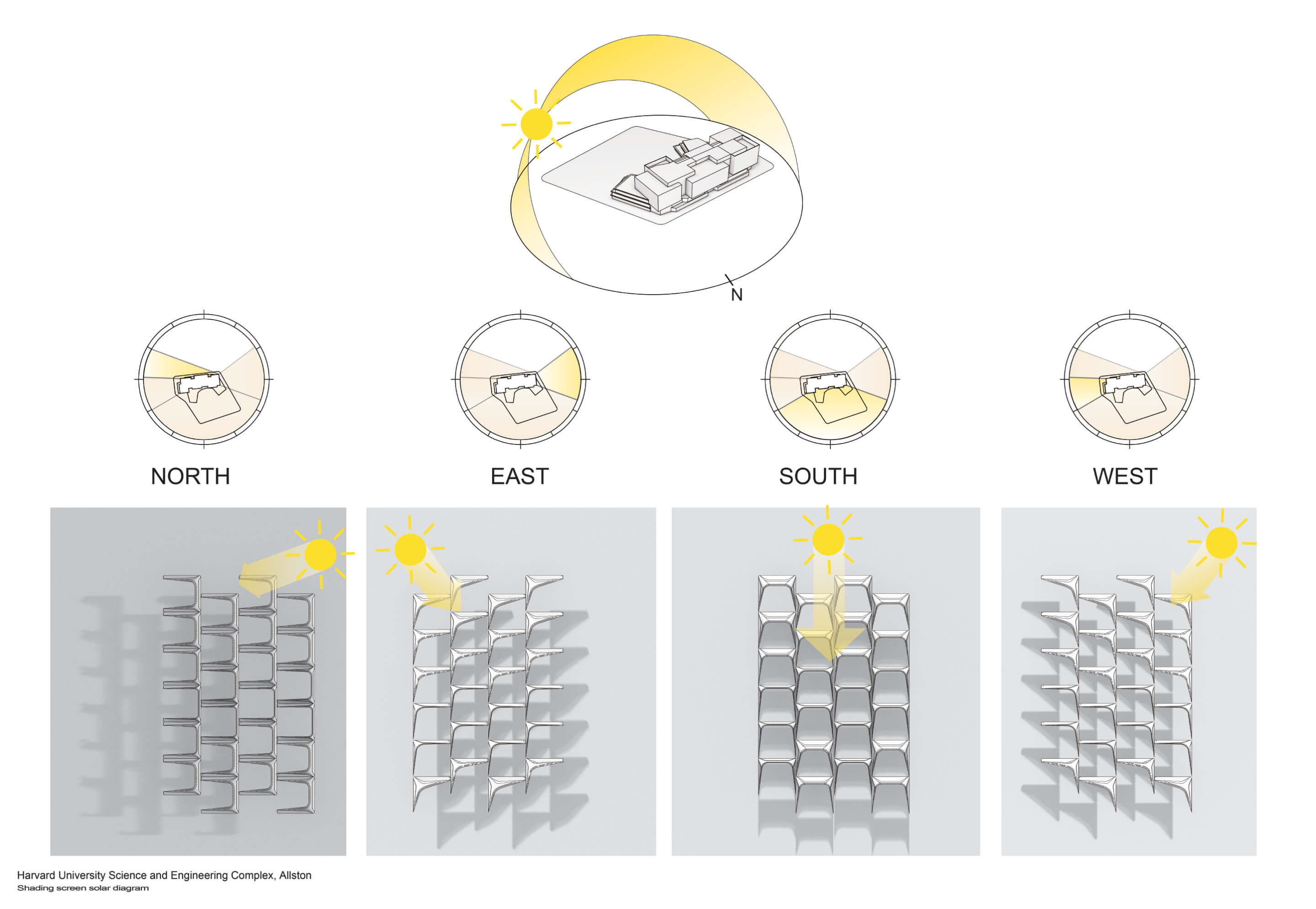

The laboratory volumes are set off by a shimmering mass of 14,000 boomerang-shaped panels, constituting the world’s first hydroformed stainless-steel shading screen. The fabrication technique, which relies on high-pressure hydraulic fluids to deform metals into complex shapes, enabled Behnisch to significantly reduce material waste. The panels block the radiant effects of sunlight during the warmer months of the year but allow daylight to passively heat the interior during Boston’s frigid winters.

Sustainability at the SEC, though, goes far beyond these window dressings. Rainwater captured on the building’s roof and in its ground-level landscaping is processed through biosoils and stored in three 75,000-gallon tanks in the basement, then recycled for irrigation and toilet flushing. Conscious of the energy-intensive ventilation systems normally required to safely operate a laboratory, Noblett and his team opted for a series of radiant heating and cooling systems to reduce energy consumption throughout the SEC. When natural ventilation through the structure’s operable windows proves insufficient, temperatures in the more interactive spaces are regulated through the floor slabs. Meeting rooms, offices, and laboratories use either chilled ceilings or chilled beams, while a uniquely efficient glycol-based coil system recovers heat energy in the complex’s roof.

Behnisch Architekten also worked closely with Harvard’s own researchers to analyze 6,000 interior finishes and select only those that were compliant with the Living Building Challenge’s Red List recommendations on chemically detrimental materials. For Stefan Behnisch, the collaboration with the university’s experts made all the difference: “Many developers treat sustainability as little more than a sales gimmick. But Harvard committed real resources, knowledge, and people to ensuring that this building would be sustainable, practical, and long-lasting.”

This project will be featured at Facades+Boston on October 26th. Register today to hear from the design team at Behnisch Architekten.

Architect: Behnisch Architekten

Location: Boston, Massachusetts

Landscape architect: Stephen Stimson Associates Landscape Architects

General contractor: Turner Construction Company

Structural engineer: Buro Happold

Climate engineer: Transsolar

LEED consultant: Thornton Tomasetti

Facade: Knippers Helbig, GmbH

Facade contractor: Josef Gartner GmbH and Permasteelisa North America Corp.

Lighting design: Bartenbach GmbH and Lam Partners

Laboratory planning: Jacobs Laboratory Planning Group

Perforated metal ceilings: Steel Ceilings

Flush wood door and interior glazing: Panello and feco-feederle GmbH

Acoustic ceiling panels: Rosso Acoustic

Exterior balance doors: Dawson Doors

Stainless steel mesh: Carl Stahl

Operable partitions: Hufcor