The new building for the Orange County Museum of Art (OCMA) in Costa Mesa, California, has spent a long time in gestation. Thom Mayne, of Morphosis, was announced as its architect back in 2008, and the building finally broke ground this past September. Now, everything is moving apace—pandemic notwithstanding—and the museum should have its long-awaited new home by 2021.

The 53,000-square-foot building—almost half of which will be gallery space—is deceptively simple in spite of its elegant flourishes. Brandon Welling, managing principal at Morphosis, described it as “a big plinth with concrete shear walls.”

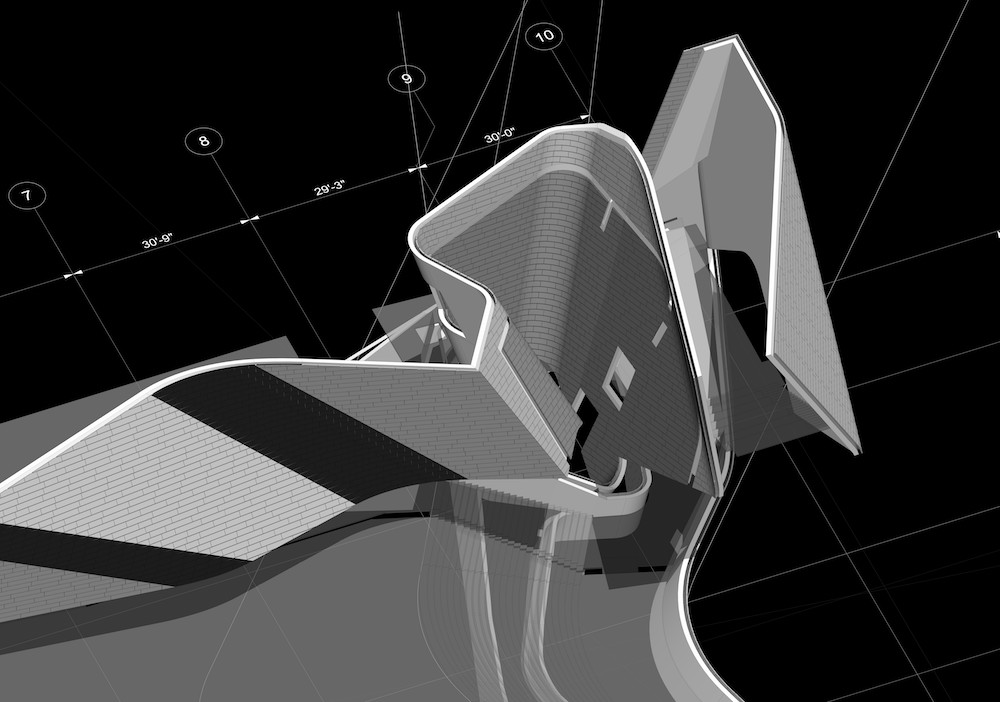

Inside that plinth will be ground-floor exhibition spaces flanked by back-of-house spaces and a curvilinear mezzanine gallery. On top of the plinth will sit an expansive roof terrace with hardscape and landscape for events and installations, bordered by support spaces and a flexible classroom and performance space.

“It’s a complicated one-story plaza building with a heavy roof load,” said Kurt Clandening, managing partner at John A. Martin & Associates, the structural engineer for the project. The roof terrace covers 70 percent of the building’s footprint.

The project will have no underground parking, so construction has proceeded quickly. Because the top layer of soil on the site wasn’t suitable for deep piles—and the noise and vibration of pile driving would have disturbed the tenants in the surrounding office towers and performance venues—the design team over excavated and used shallow foundations. This provided the opportunity to sink the building slightly. Welling described the design as returning park area to the adjacent plaza by lifting it up to the rooftop terrace and inserting the museum underneath.

The museum is the last building to go into the Segerstrom Center for the Arts, a cultural complex tucked into a corner of a larger mixed-use plaza. Surrounding buildings include a 21-story office tower to its south and a concert hall to the west, both designed by César Pelli. Another performance venue sits across a plaza to the north. The architects were careful to select materials that would help the new building fit in well with these neighbors, including a light-colored terra-cotta for the facade.

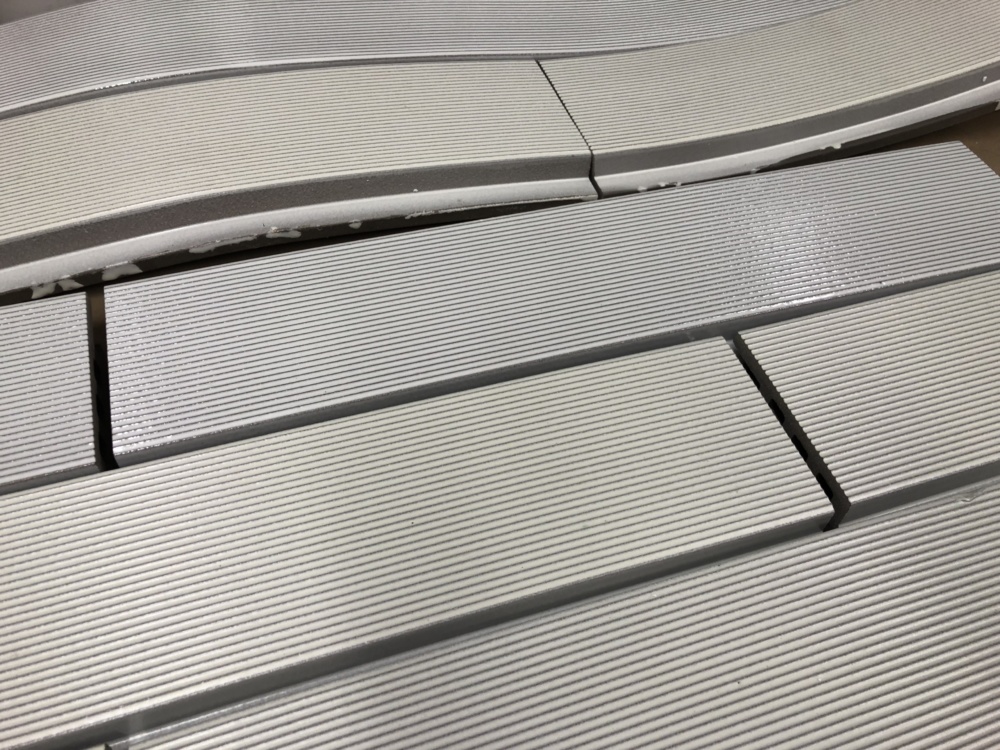

Morphosis had been in discussion with Boston Valley Terra Cotta about working together on a project and the museum presented the right opportunity. It helped that the manufacturer was willing to push terra-cotta’s typical uses, as the complex curves of the building’s facade are its signature gesture.

“The terra-cotta is like a fabric woven through the building,” Welling said. “It’s a continuous strip that starts at the end of the upper facade on the terrace and weaves into the lobby, down through the atrium and across the front facade.”

To get the terra-cotta to match Morphosis’s design—a process that has required constant communication—the panels are cast and then slumped over forms. Judging from the samples, the result will be luminous and tactile, important qualities for a museum striving for a welcoming effect.

The new museum faces a plaza renovated in 2017 by Michael Maltzan Architecture, which prompted the Morphosis team to choose pavers for the area around OCMA that mixed precast concrete with the stone from the plaza. These pavers work their way up to the glazing at the front of the building, and the patterning continues inside. The pavers are used again on the roof terrace to connect it visually to the plaza below.

“We’re always looking for opportunities for the ground plane to continue from outside to inside,” said Welling, so that the experience on one side of the glazing is not radically different from the experience on the other side. The museum will have a 1,500-square-foot gallery that runs along the Avenue of the Arts on its east side, allowing passersby to see the artwork on display.

Most of the building’s complexity—those swoops of terra-cotta on its north side—centers upon the classroom and performance space on the terrace level. The space, which is just over 1,000 square feet, is cantilevered over the plaza and hovers over the atrium inside the building. A multilevel, floor-to-ceiling window overlooks the terrace and the plaza below it. Clandening described the multistory space, which features curved and angled surfaces on both the interior and exterior, as “a geodesic box inside a geodesic envelope.”

The museum has needed more space for decades to show its permanent collection, which now numbers some 4,000 pieces, while continuing to program changing and traveling exhibitions. The new building gives the museum an additional 15,000 square feet but is smaller than Mayne’s original unbuilt 2008 design, or what had been proposed in earlier expansion plans. To give OCMA future flexibility, the roof has been designed to accommodate a one-story addition, which would enclose an additional 10,000 square feet on the south side of the terrace.

OCMA’s new building fills the last open space within the Segerstrom Center for the Arts—one that’s been held for it for a very long time. When the museum opens on the plaza, it will be a welcome and stylish addition.