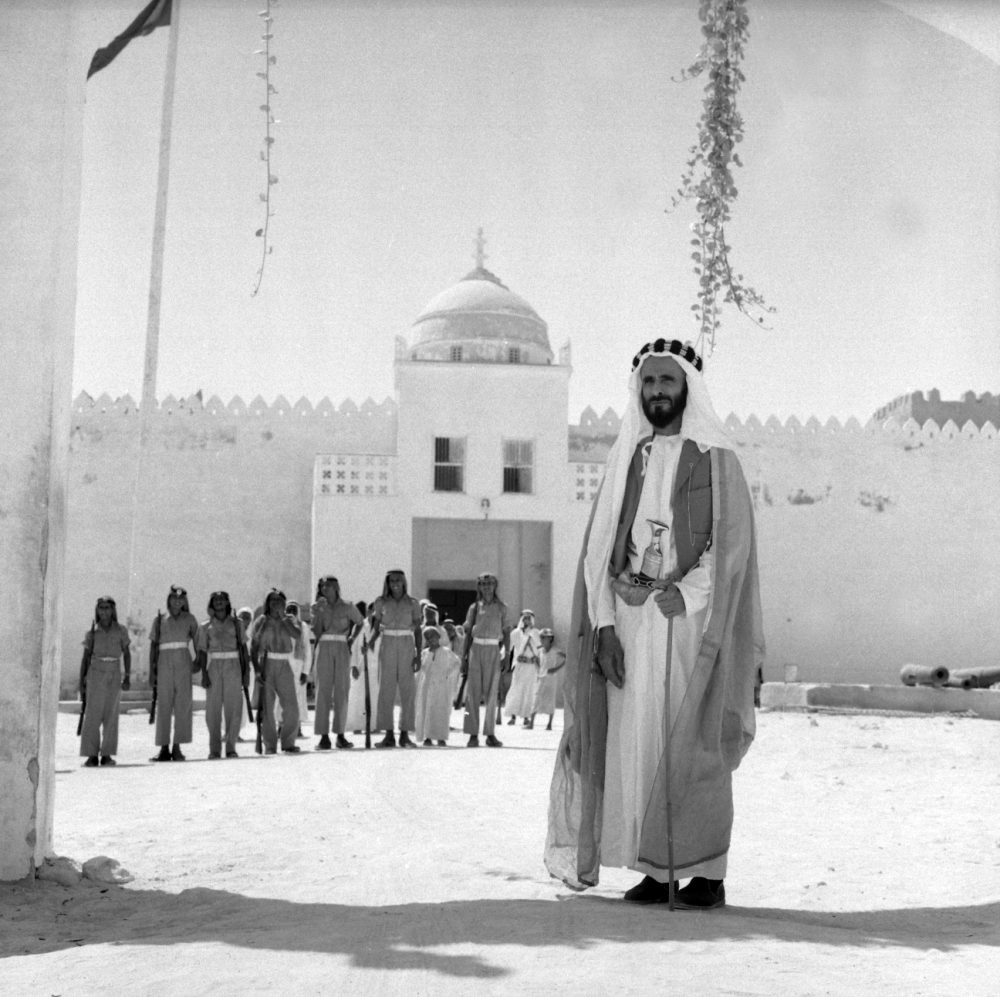

Architectural heritage is something of an anomaly in the city of Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates. Since 1950 the city has grown from 4,000 residents to nearly 1.5 million, many of whom are housed and working in miles-long rows of concrete tower blocks. The 18th-century Qasr Al Hosn castle stands as a rare historical monument in this remarkably modern city, and the local government just recently completed a decade-long architectural conservation program restoring and stabilizing its masonry walls.

The Qasr Al Hosn was built by the ruling Bani Yas tribe in the 1760s as a coastal bastion defending the city’s fresh water well and regional trade routes. The walls and towers are built of coral and sea stone and are lathed in a render composed of burned and crushed seashells mixed with white sand and water. Rich in minerals, the render takes on a bright white and iridescent finish that glints under the sun.

Apertures are located throughout the concentric rings of walls, naturally drawing ventilating gusts throughout the complex. And as a virtue of the thermal mass of the formidable walls, the sequence of courtyards is considerably cooler than the surrounding city.

After centuries of wear and tear, as well as the ill-thought coating of the original masonry with a thick cementitious render and decorative layer of white gypsum, the castle was due for a significant restoration.

The restoration of historic structures, especially those of major cultural significance, requires painstaking material and historical research. The Department of Culture & Tourism (DCT) deployed a team to “carefully remove strips of the modern render layer which enabled us to determine that a high extent of original masonry was still intact and to discover that the original render was still in existence in areas,” said Mark Kyffin, DCT Head of Architecture. “This enabled us to analyze the constituent parts of this material, under laboratory conditions, for replication and application in the ensuing remedial works.”

With the information gathered by laboratory observation, the team developed a new render replicating the porosity and thermal qualities of the old. Research of preexisting masonry sections also provided insight into its original hand application, a process appropriated by the modern construction team.

While the use of render shields masonry from the elements—think of it as a coated rainscreen—the condition of loadbearing elements determines the structural longevity of the building. The walls that surround the complex are just under two feet in width, with significant voids caused by internal stone deterioration. To fill these voids, the DCT set up a gravity-injected mortar grouting system.

“Loose mortar was removed from the external facing masonry joints and temporarily replaced with cotton wool,” said Kyffin. “This enabled the wall to be a sealed enclosure and prevented grout from seeping through the facade.” The external cotton wool was removed once the internal grout had cured, with gaps in the masonry subsequently being repointed.

Historical research also played a significant role in the conservation process. Researchers pored over photographs, diary extracts, and oral testimonies of those who lived in the building during the 1940s, gaining further knowledge of key building features.

Abu Dhabi is surrounded by desert. For centuries, the city exclusively sourced its timber from an adjacent and expansive mangrove forest. The dimensions of internal rooms were dictated by the maximum height of the local mangrove forest; the tallest mangrove poles can measure close to twenty feet.

In conjunction with the restoration of the Qasr Al Hosn, the Department of Culture & Tourism collaborated with Danish architecture firm CEBRA to landscape nearly 35 acres of open land surrounding the castle. Also unveiled in December, the design features polygon-shaped concrete formed to resemble the sun-baked earth and rolling water features that course pass shade-providing vegetation.