Should New York’s Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) support a proposal that continues a 40-year-old design approach by an esteemed architect, even though it’s not what environmentally-sensitive architects would propose today? That was the question was raised during the June 2 LPC hearing, as panel members discussed whether to approve a new south-facing glass wall for the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing of the Metropolitan Museum in Art.

This followed a February meeting where the commission expressed concern over the scope of proposed changes. The curtain wall was proposed to replace a 1982 glass wall originally designed by Kevin Roche that has worn poorly after decades of exposure to direct sunlight.

While wanting to respect Roche’s original design, several commissioners asked, were they ignoring lessons learned over the past four decades about creating energy-efficient buildings? Does it make sense essentially to swap out one glass wall for another in a world-class museum that has priceless light- and moisture-sensitive works of art inside?

“The real conundrum of this facade is that they’re stuck with this design that is just wrong for this location,” said commissioner Michael Goldblum. “A bolder approach would have been a rethinking of the facade as an esthetic composition to one where shading or different materials or other approaches were taken to reimagine this south-facing facade in a way that was more environmentally-sensitive.”

“How presumptuous were they to think that you can build a glass wall facing south and you’re not going to have any problems with it? Just insanity,” agreed commissioner Michael Devonshire. “If they had come to us with a completely different aesthetic, it may have been met with a lot more approval early on.”

Still, the panel voted 9-to-0 to accept as “appropriate” the design proposed by the museum and project architect Beyer Blinder Belle.

The vote helps pave the way for the museum at 1000 Fifth Avenue to begin work on a $70 million project to renovate, reconfigure, and reimagine the Rockefeller Wing, which houses the museum’s collection of art from Africa, Oceania, and the Americas.

Thai architect Kulapat Yantrasast of wHY Architecture has been named the exhibition designer for the 40,000-square-foot space. Work was originally scheduled to begin in late 2020 and be completed in 2023 but has been pushed back, pending LPC approval.

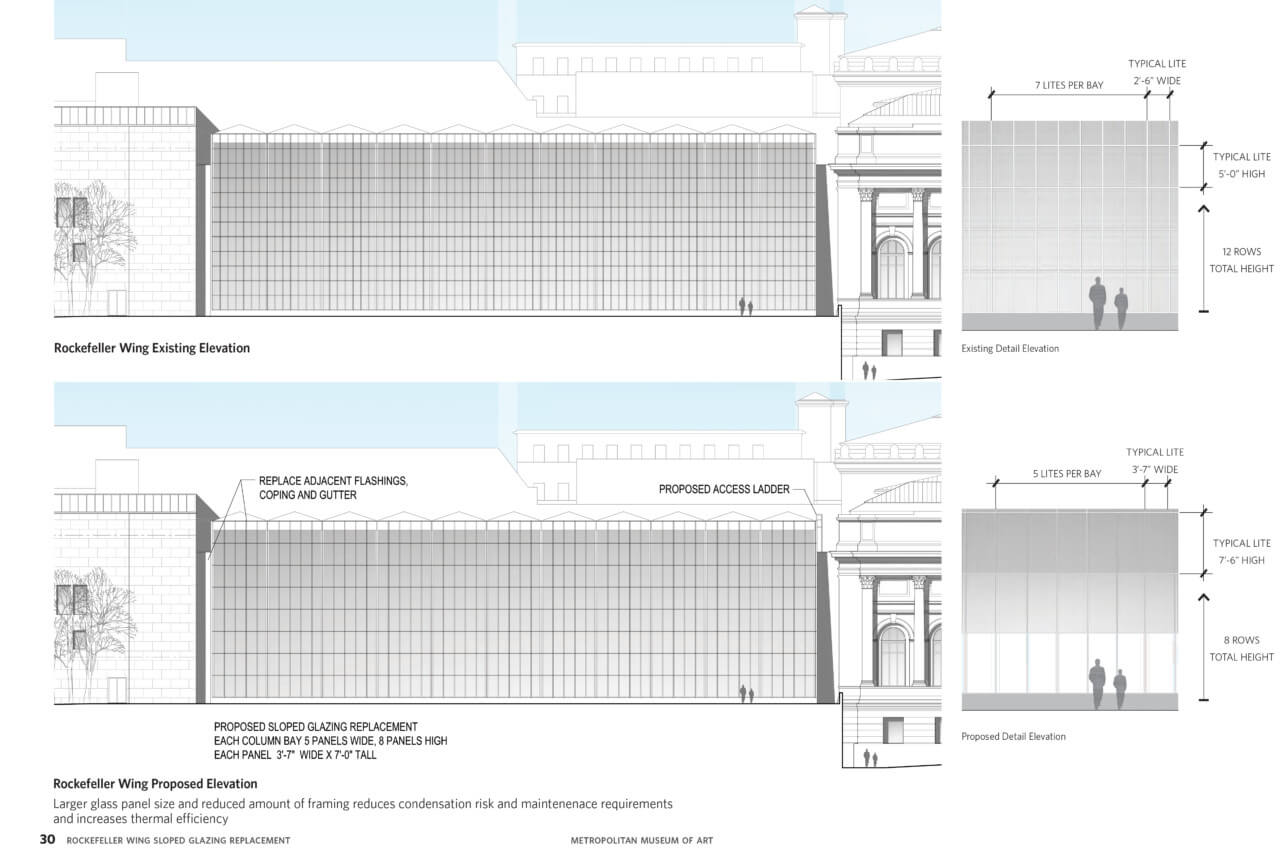

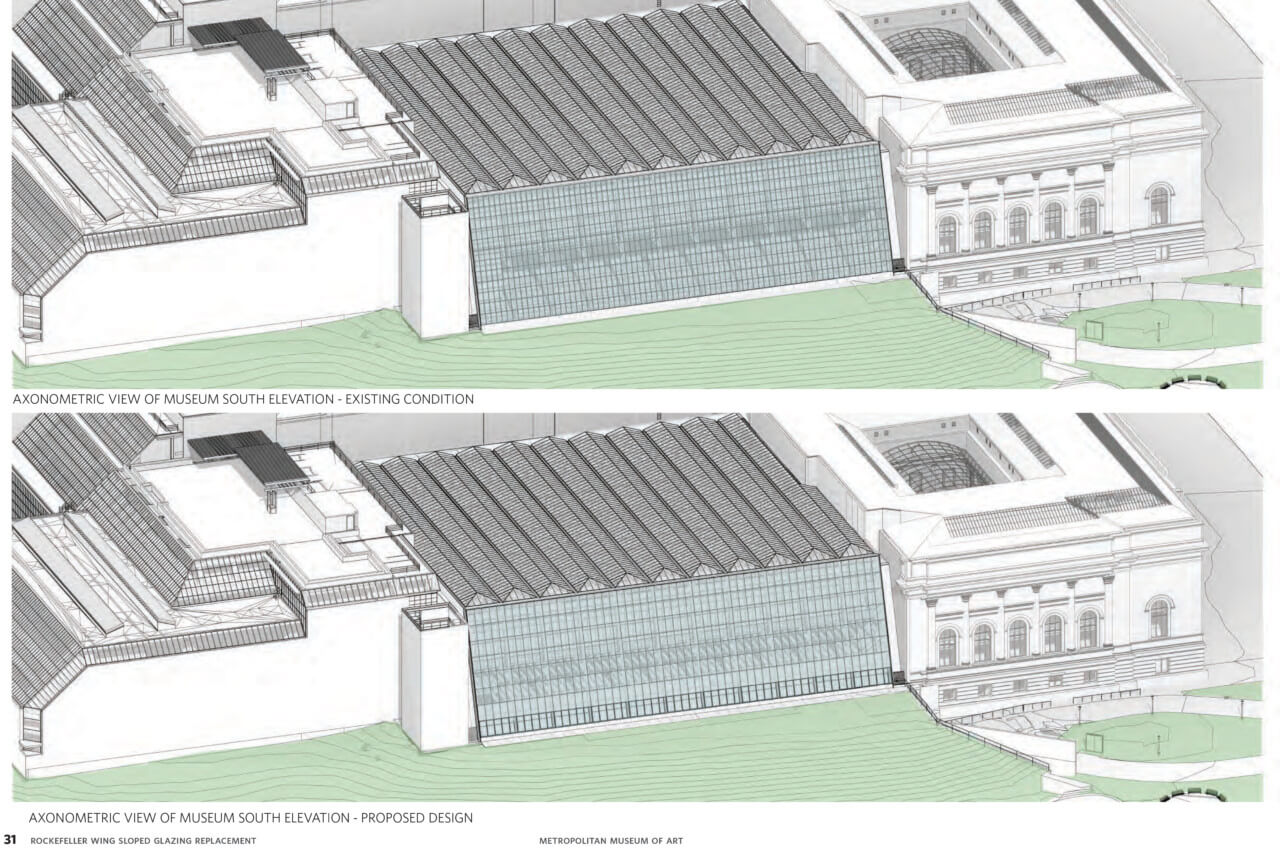

As approved by the LPC, the design calls for the replacement wall to slope at the same 20-degree angle as the existing wall, but with different-sized panes of glass, a different method of holding the glass in place and a different frit pattern on the glass. Like the existing wall, it will be 200 feet long and 60 feet tall.

The unanimous vote came after chair Sarah Carroll told the commissioners that Eamon Roche, son of the late Kevin Roche and managing director of the firm his father founded with John Dinkeloo, now called Roche Modern, supported Beyer Blinder Belle’s approach. That seemed to be a key point in the deliberations, after Roche raised questions about the design during a hearing on February 9.

“We respectfully find the aesthetics resulting from the proposal to be a bit of a loss,” Roche told the commission during its virtual meeting in February. “There are three principal design elements at play in this proposal and we feel that at least two of them could be handled differently to ensure the architectural result is both better and more historically in keeping with the original design.”

Roche did not speak at Tuesday’s hearing because the commission was not accepting public testimony about the project. But, in a May 20 letter to Beyer Blinder Belle partner John H. “Jack” Beyer, on file with the preservation commission, he backed the latest design.

“Given your firm’s past history, Roche Modern has great confidence that this difficult assignment has been placed in the right hands and you have our full support,” Roche wrote to Beyer.

Michael Wetstone, an associate partner at Beyer Blinder Belle, said that from the start that his team wanted to find a solution that adhered to the 1970 museum master plan developed by Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo to guide individual expansion projects such as the Rockefeller wing.

He told the commission that his team’s research showed that Roche proposed a glass facade for the Rockefeller wing as a way to make it come across as an extension of Central Park to the south, not an intrusion.

Wetstone said that the idea of alternating glass walls and stone-clad walls was a key tenet of the Roche-Dinkeloo master plan, and he noted that the Rockefeller wall is a “twin” to the earlier, sloping wall on the Sackler/Temple of Dendur wing on the north side of the museum.

When the master plan was approved in 1970, “there was still some concern about expanding into the park and taking parkland,” he said. “So one of the things that Roche-Dinkeloo did is to have alternating additions of limestone[…]and additions that were made out of glass that were transparent and looked like outdoor rooms. The idea here was that the glass rooms would be a museum with a wall around it but would really appear to be almost a natural extension of the park. That was the intent that Roche had expressed.”

Wetstone said the team, including Arup, wanted to increase the size of the glass panes – from 2’ 6” wide and 5’ tall to 3’ 7” wide and 7’ 6” tall. They wanted to change the framing system that holds the glass in place from a captured glazing system to a structural glazing system, with silicone joints visible between the glass panes instead of aluminum mullions covered by raised metal caps. The design team also recommended a more gradual approach to darkening the wall from bottom to top so the facade wouldn’t read like distinct rows of glass.

Roche asked the Beyer Blinder Belle team in February to keep the original glass pane size and the raised caps, saying the proposed changes represented a departure from the Roche-Dinkeloo design. Wetstone told the commission Tuesday that his team considered Roche’s suggestions and discussed them with the museum staff.

In the end, Wetstone said, his clients at the museum didn’t think smaller panes of glass or the original structural system would meet the Met’s current climate control requirements and they didn’t accept Roche’s suggestions. One change that Beyer Blinder Belle did make, Wetstone said, was to lighten the color of the outer silicone seal visible between the glass panes, but still make it perceptible so the facade will read as a grid and not a sheer plane of glass.

Roche said in his May 20 letter that he had a chance to consult with Beyer Blinder Belle’s team and learn more about the technical issues associated with replacing one glass wall with another.

“Perhaps in time, a hybrid glass/metal cassette system might be available but at present this approach is not engineered, tested or ready for the marketplace,” he wrote. “Therefore, we accept the limitations of the elements that your firm could design[…]when it came to detailing this facade.

The commissioners talked about the proposed glazing details, apart from the environmental considerations. Several questioned how easy it would be to keep the silicone clean. Shamir-Baron said she would prefer a narrower joint but ultimately said she could accept the proposed width. After a majority of the commissioners indicated they could find the design appropriate, aside from the environmental concerns, the matter was put to a vote.

Wetstone said the museum intends eventually to replace the sloping curtain wall on the Temple of Dendur wing but has no schedule for that work. He noted that the museum doesn’t have the same pressing solar issues with that wall as it does with the Rockefeller Wing wall because it faces north and isn’t exposed to direct sunlight.

Goldblum suggested that the preservation commission attach a note to its file on the Rockefeller wing so city staffers have a record of all the research and analysis that went into the glass replacement issue for when the Temple of Dendur wing comes before the board.

Of all the commissioners, Goldblum was the most direct in saying he would have been willing to entertain a wider range of energy-efficient proposals for the Met and not just limiting the options to variations on another sloping glass wall. “But that,” he said, “is not what we have before us.”