Los Angeles’s Sunset Strip is a charming hodgepodge where buildings old and new jostle for space with palm trees and rotating billboards. Adding to this riotous scene is a new urban marker every bit as attention-grabbing as Hollywood blockbusters and architectural kitsch. At 67 feet tall, the West Hollywood Sunset Spectacular is somewhere between a billboard and a Transformer.

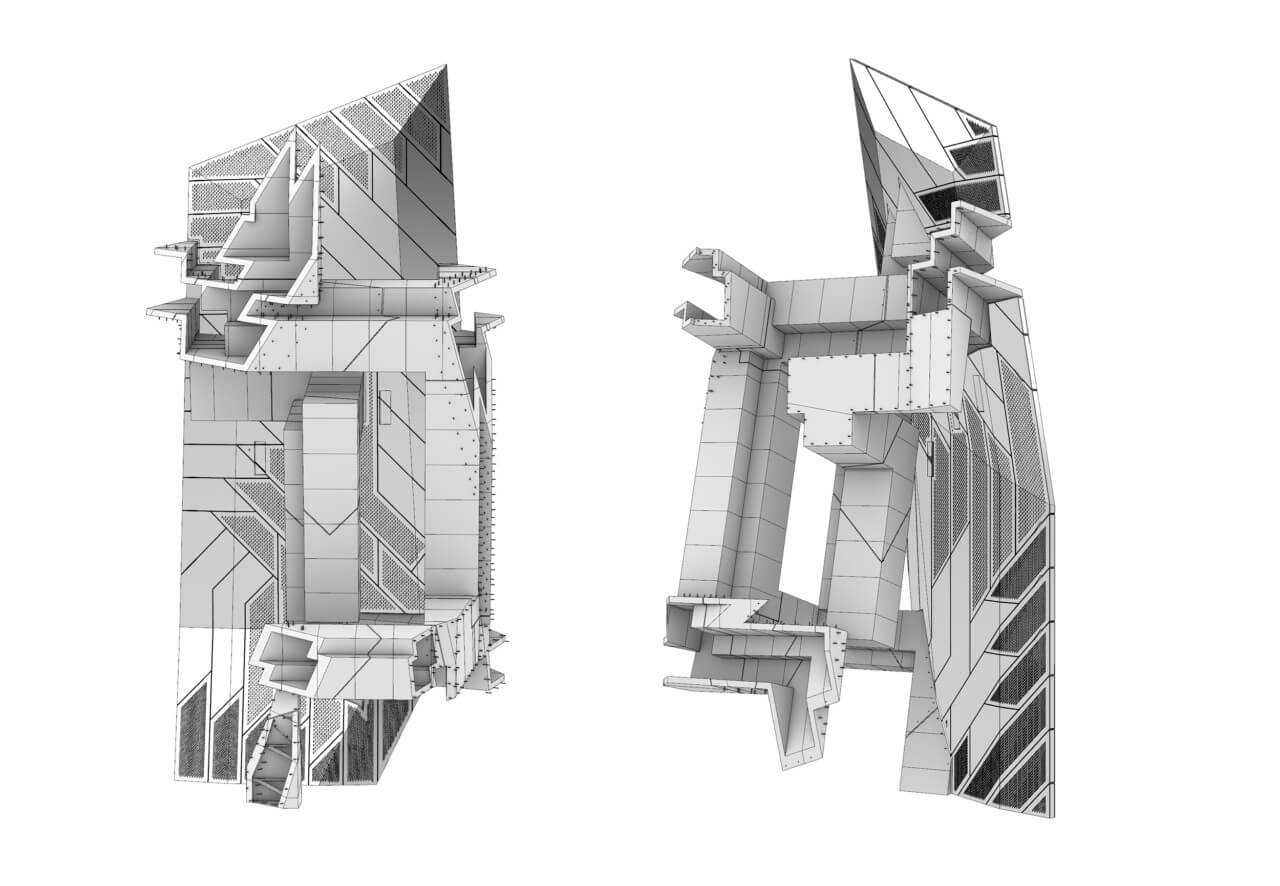

Massive multimedia displays beam out advertisements every few seconds, while oversize stainless-steel modules give the impression that the shardlike obelisk could suddenly click into gear.

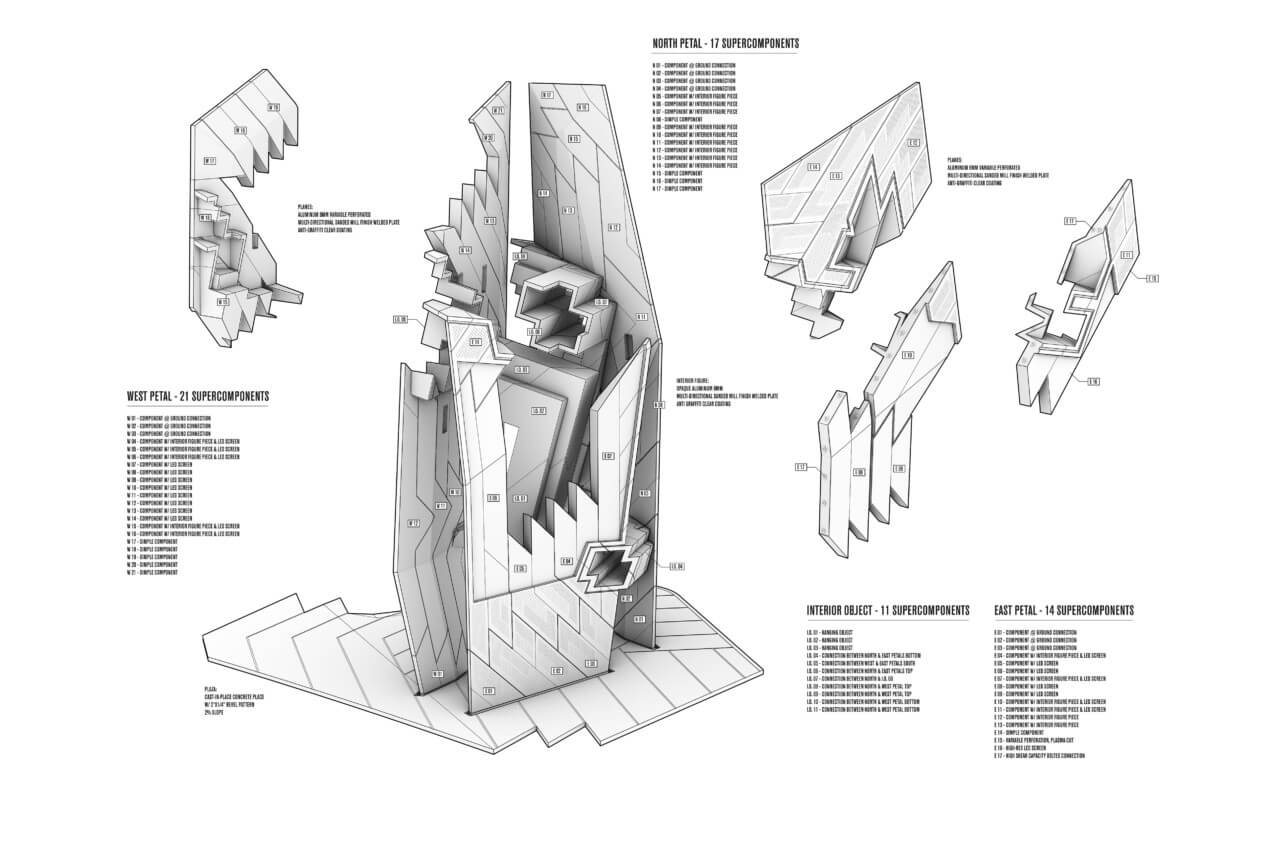

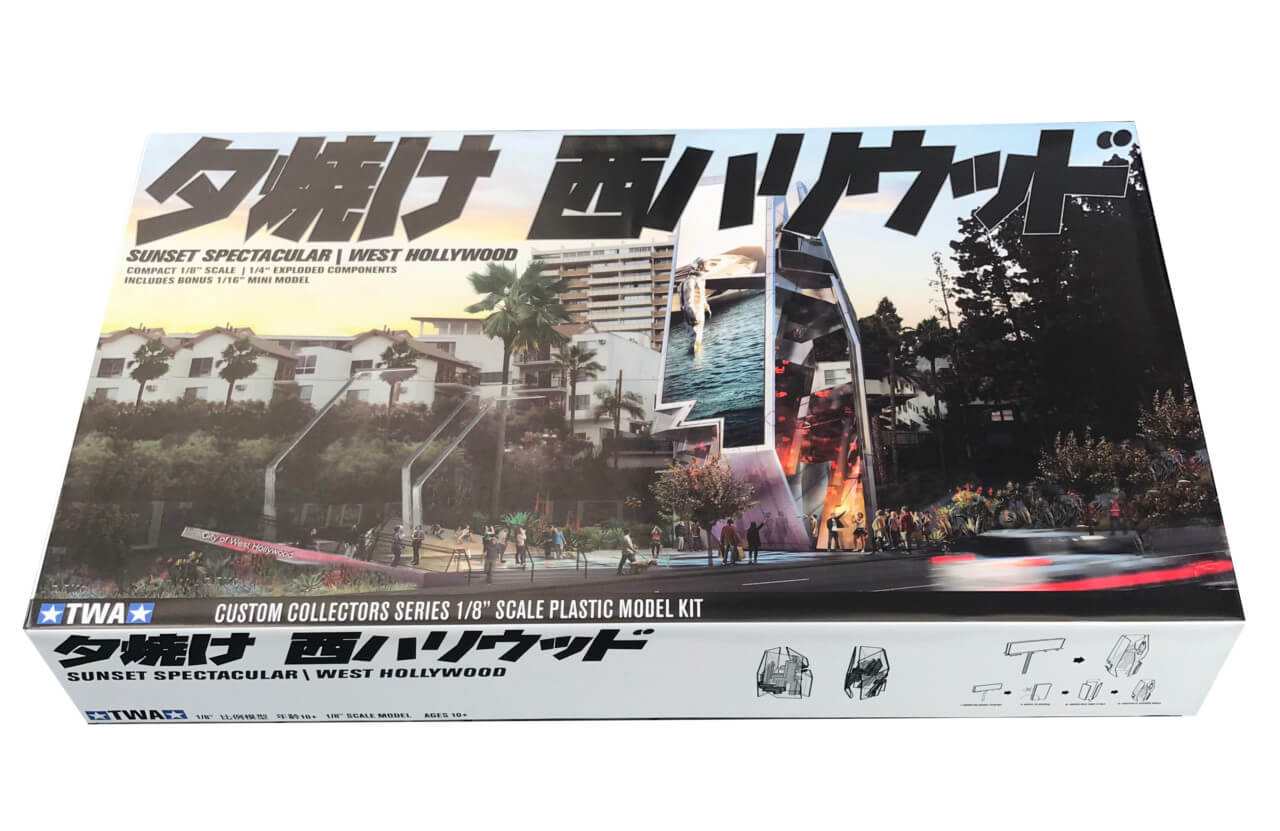

Local firm Tom Wiscombe Architecture (TWA) developed the project alongside Orange Barrel Media for a 2016 city-sponsored competition, fending off stiff challenges from the likes of Zaha Hadid Architects and Gensler. In the several exploded diagrams that TWA prepared for its submission entry, the assembly of the individual building pieces mirrors that of a model set. “It’s really the only kind of architectural representation that I trust,” said founder Tom Wiscombe.

That playfulness, however, belies the unorthodox construction techniques, advanced design-assist processes, and complex systems integration marshaled for the project’s realization.

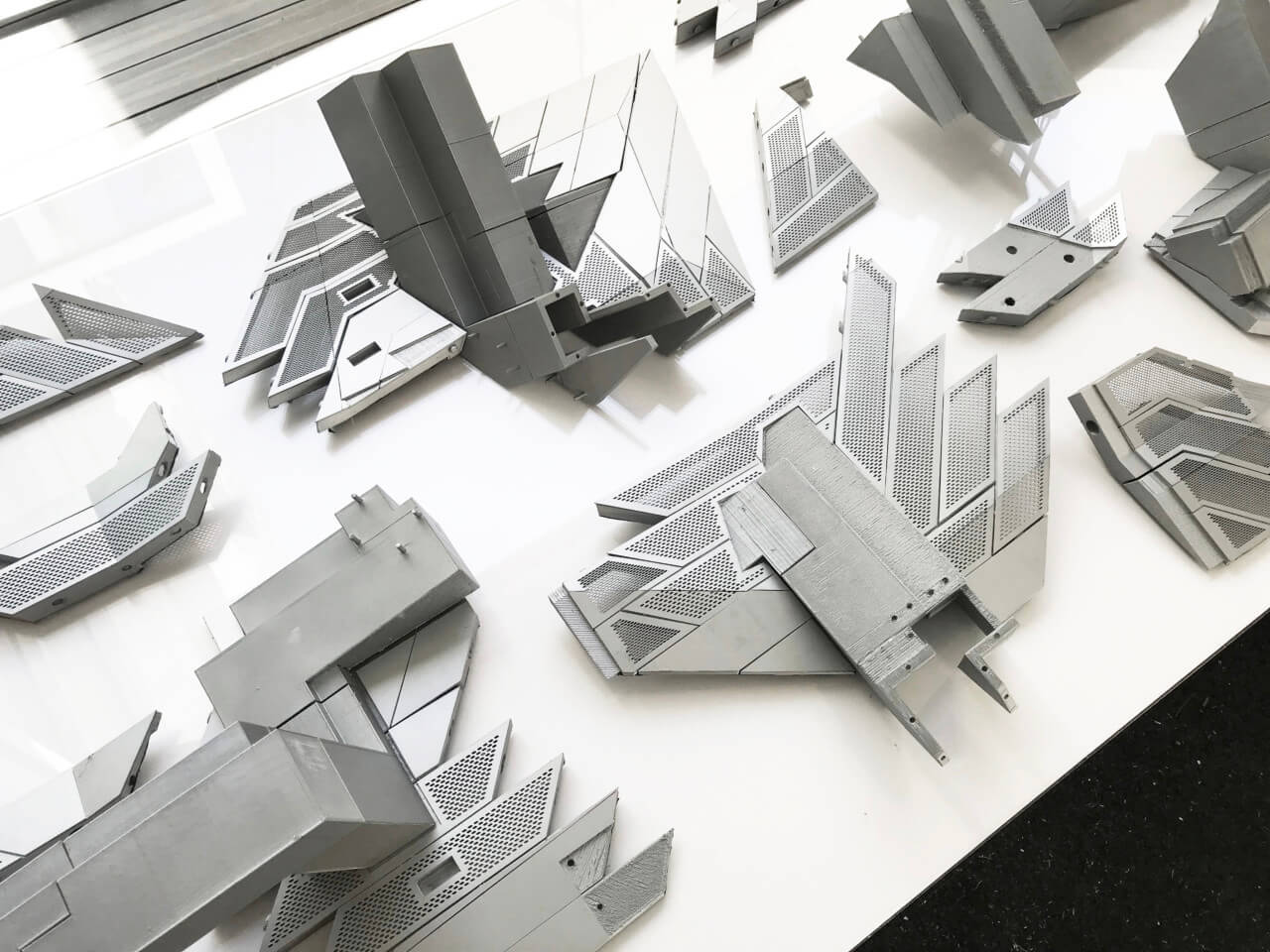

Early on, structural engineering firm Walter P Moore determined that a standard frame-and-skin enclosure system would be too expensive and instead suggested welding TWA’s componentry together in a process akin to aircraft construction. Its fabrication fell to Northern Manufacturing, an Ohio-based maker of industrial equipment, with construction modeling firm DBM Vircon acting as a go-between. (Project detailing was key to avoiding errors in prefabrication that could prevent the components, each one entirely unique, from aligning on-site.) The Los Angeles office of MEP engineers Glumac devised an intensive electrical system capable of powering 1,500 square feet of digital tile, three high-powered laser video projectors, and multiple sound systems.

The entire enterprise breached the boundaries of the architectural, passing into the infrastructural: Altogether, 100 tons of stainless steel went into the construction. The components—or, per Wiscombe, “superstructure chunks”—were loaded onto 770-foot-long super-load lowrider trailers for the 2,300-mile trek west. Each piece arrived on-site in West Hollywood with a loose back panel that allowed them to be bolted together on their perimeter faces. (That connection was subsequently concealed.) A 90-foot-tall industrial crane hoisted the “chunks” into place; arranged in three towering panels, they form a cocoon around a pedestrian-accessible central void. Suspended overhead is a sculptural entity that appears to stabilize the heaving mass.

For Wiscombe, the project forcefully challenged industry paradigms. “It is time that we really take apart how we build, what kinds of elements are used to build, who builds it, and how we document it,” he said. “One thing that I’m really proud of on this project is that we didn’t accept anything that was given on any of those fronts, we are kind of working as skunkworks, and there is a bit of mystery shrouding what is being done. I view that as a mode of innovation.”