The Portland Building, located in the downtown of its eponymous city, is hard to ignore. Designed by Michael Graves Architecture (MGA) and completed in 1982, the tower is something of a monument to the Postmodern architectural movement and served as a stepping stone for Grave’s larger body of work across the country. The project’s facade is unabashedly playful and is festooned with exaggerated architectural elements, from rusticated facade panels to pediments, and even an oversized Classically-styled sculpture rising from an arcaded turquoise podium. However, in a predicament familiar to any architect, MGA accommodated a tight municipal budget through budget engineering, which led to a host of building systems failures and muted design flourishes.

For DLR Group, the extensive overhaul of the tower, which was completed in 2019, is as much a story of correcting technical flaws as it is reestablishing MGA’s original design concept for this civic landmark. The project dates back to 2012 when the City of Portland contracted consultant The Facade Group (now part of RWDI) to conduct an assessment of the facade condition in conjunction with an interior survey led by a team of architects. DLR Group and Howard S. Wright Construction was awarded the project in August 2016 and followed a progressive design-build delivery model, which looped in collaborators such as Benson Industries and KPFF Consulting Engineers from the onset.

Even when adjusted for inflation, the original construction budget in 1982 of $20 million was a paltry sum in comparison to contemporaneous projects, and, as a result, materials and systems shortcuts were chosen over long-term durability and performance.

“Many people don’t realize that the original building was primarily painted concrete with mortar set ceramic tile at the base; and the facade didn’t have any internal water management capabilities, so the whole envelope was relying solely on sealant joints. This strategy started failing almost instantly, and the City was dealing with constant building leaks within the first 10 years of the building’s completion,” said DLR Group senior associate Erica Ceder. “The ceramic tile system, which was tile set on mortar over metal lath—was equally problematic. The system was efflorescing immediately after installation as the water that got behind the system either escaped through the grout joints or remained trapped behind the tile.”

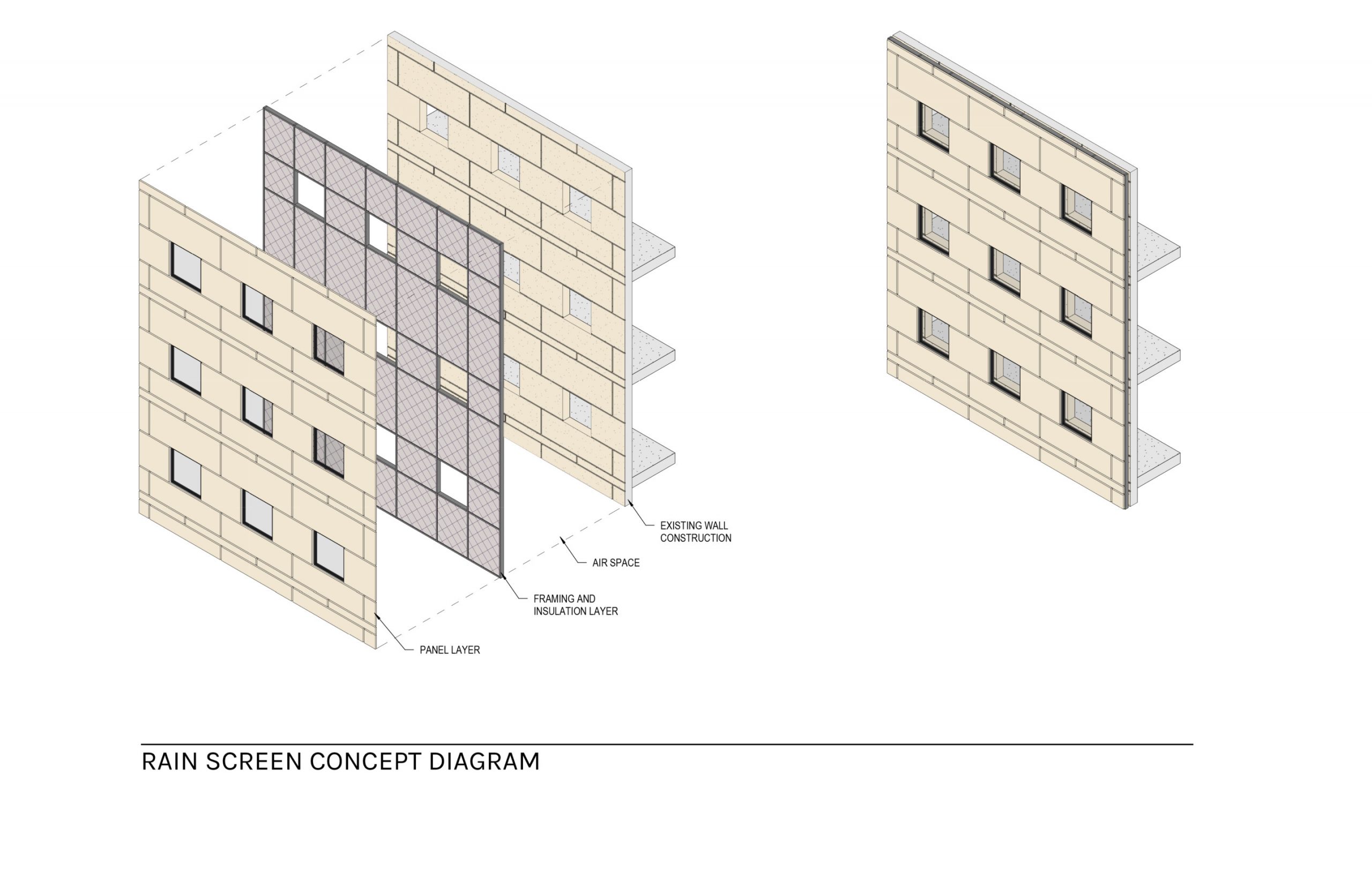

The failure of the facade system presented two primary conundrums for the design and engineering teams to overcome: detailing a new enclosure in line with present high-performance standards and visually replicating MGA’s original design, all while ensuring a straightforward installation schedule. The solution was a custom-unitized facade system, developed by Benson Industries, of painted aluminum plate panels installed over a new framing and insulation layer placed atop the existing concrete exterior, and tied to the primary volume with structural clips. The range of features found in MGA’s original design limited the degree of repetition found in the unitized system, which warranted the fabrication of mock-ups for each panel type to gauge color compatibility, surface treatments, and detailing. A similar process was conducted for the new terra-cotta tile system found at the tower’s podium.

Despite the host of flaws found in the original facade system of the Portland Building, the tower is nonetheless listed by the National Trust for Historic Places and the design team had to back up their approach with constant dialogue (some would say diplomacy) and extensive research. “Currently, the rules of historic preservation have a strong focus on retaining original materials or replacing materials ‘in kind’. That really poses a challenge for these modern and postmodern buildings where the materials are factory produced and don’t have the same centuries-long track record as the materials from previous eras,” continued Ceder. “We spent a lot of time researching, studying precedents, exploring alternatives, and consulted multiple times with Michael Graves’s office on our proposed solution. Ultimately, our team believes that over-cladding the original building was the solution that allowed us to stay true to the original design expression, while not replicating the flawed performance details. And thankfully we were able to make a strong enough case for this approach to receive unanimous approval from the Portland Historic Landmarks Commission.”