A different conversation about the capabilities of 3D-printing is happening at edg, a New York architecture and engineering firm which focuses on technology-driven design and the restoration of buildings. For the past five years, edg has been engaged with research into the combination of 3D-printing technologies and methods of casting in concrete.

Inspired by the initial buzz surrounding 3D-printing within architecture, Founding and Managing Partner John Meyer and his team began prototyping with a small MakerBot Replicator Z18. The desire was to move the conversation beyond small, fragile parts and into real-world implications of methods in additive manufacturing. Rather than focusing on solid 3D-printed parts, which are usually expensive but aren’t durable or aesthetically pleasing, edg’s research team began investigating the potential of 3D-printing as a method of complex concrete mold-making.

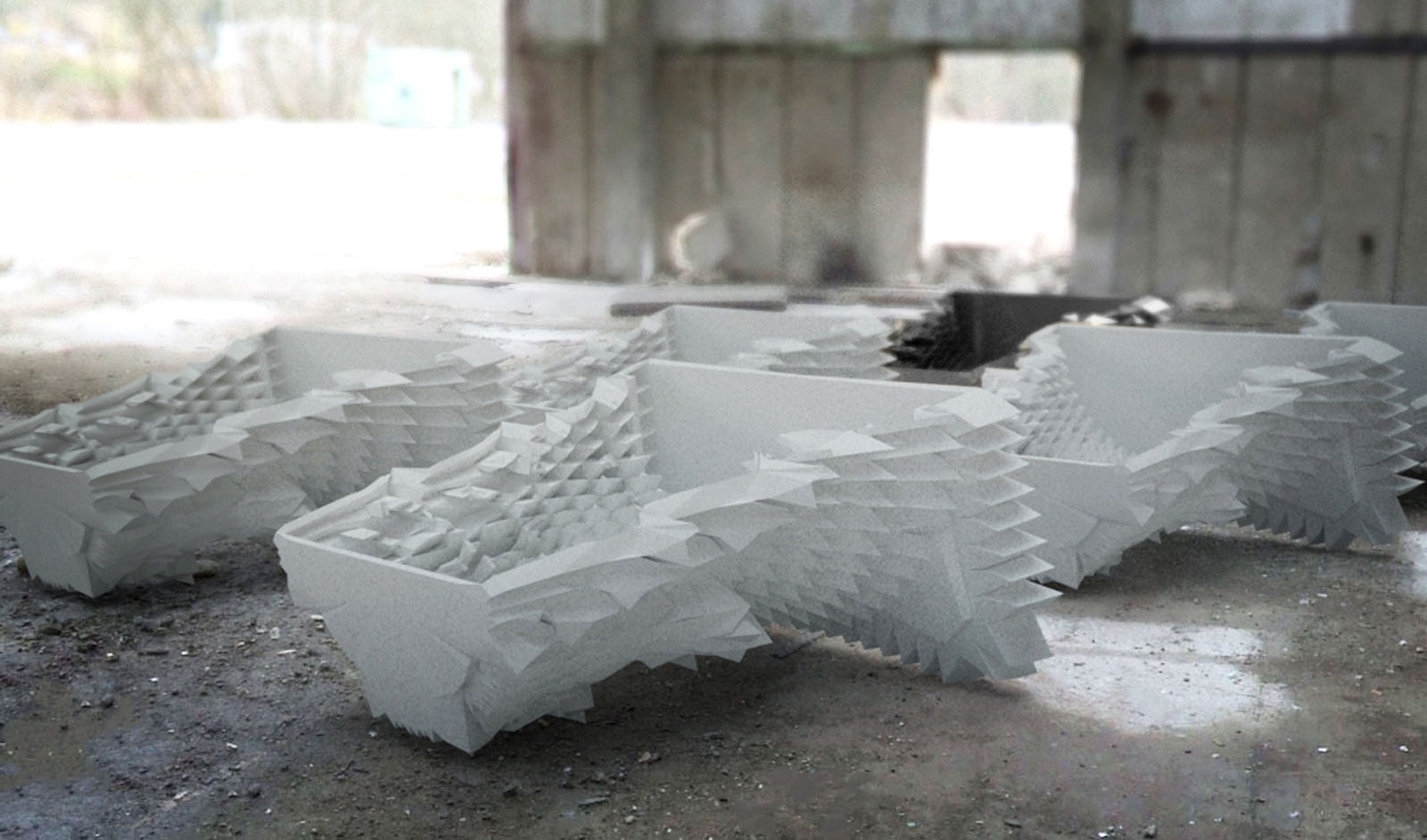

The research implications were amplified once edg understood how to apply it. When it learned of the impending demolition of 574 Fifth Avenue, a 1940 building with intricate ornamentation, edg turned the project into a case study, a perfect prompt for thinking of alternative ways to restore and maintain deteriorating ornamentation. Conducting its fabrication work on a rooftop near its New York office, edg exhaustively explored materials and mold thicknesses until the team arrived at what it considered to be the right combination of material cost efficiency and strength.

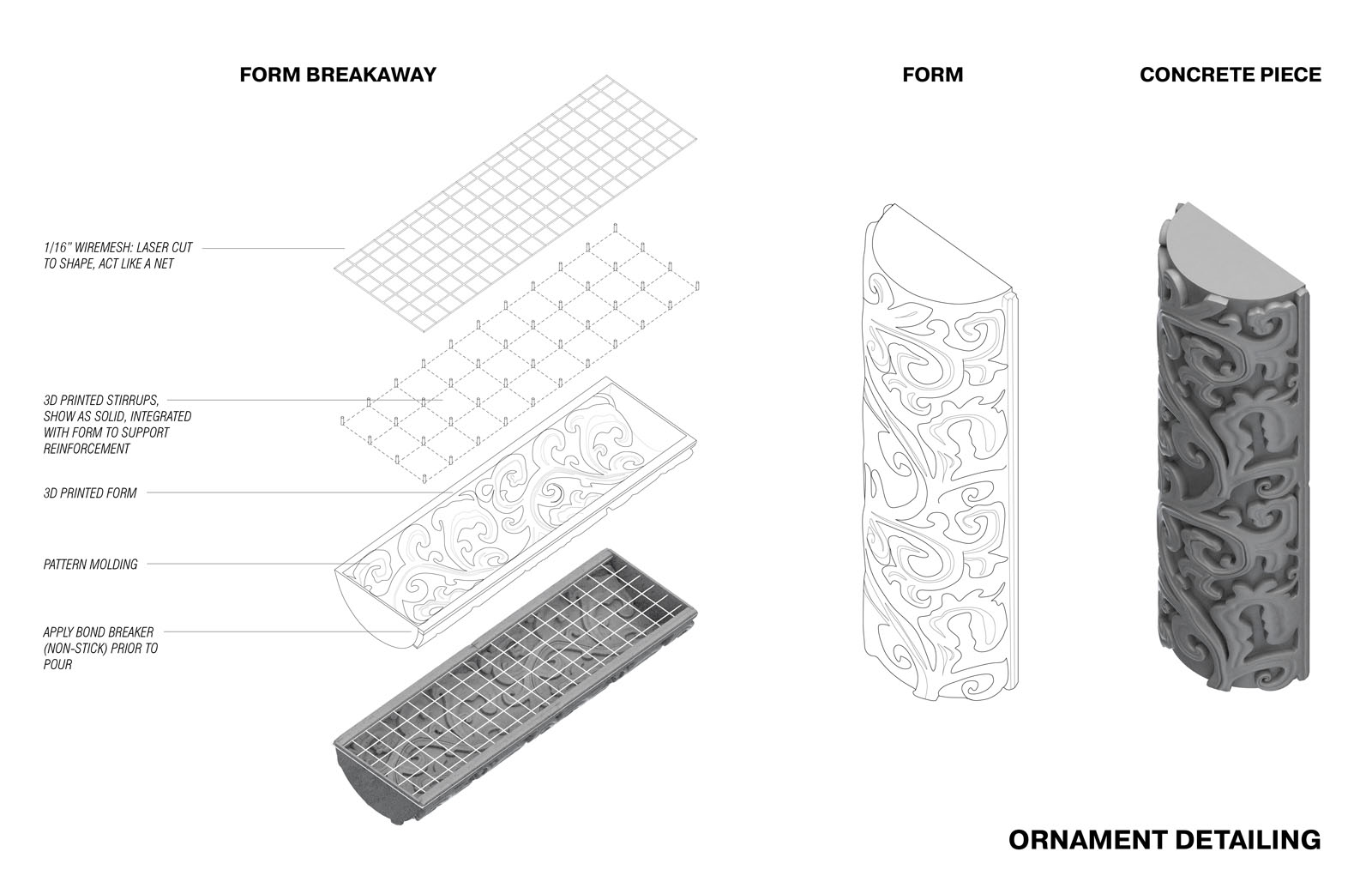

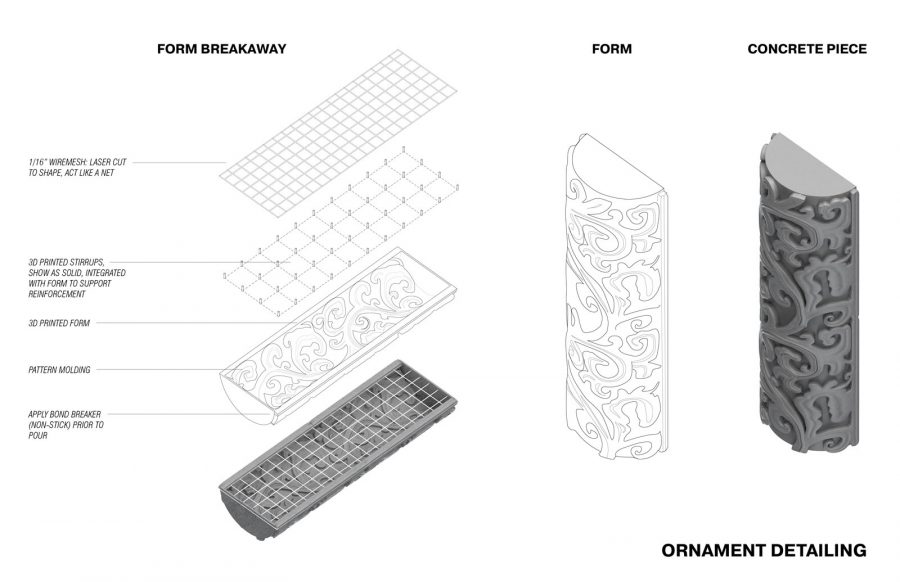

As seen in the firm’s prototypes and its diagram of the assembly, the 3D-printed plastic form is inlaid with a laser cut wire mesh as well as stirrups to provide reinforcement for the cast. Edg also designed a simple plate connection system which is formed into the printed area to facilitate easy attachment to the facade. The final prototypes were manufactured by VoxelJet using their VoxelJet VX1000 printer for the casting molds and were fabricated in-house with Sika concrete.

This project has far-reaching implications for historic preservation, but this research isn’t nostalgia for lost fabrication techniques: it has broader possibilities within facade construction and design. As edg stated in a press release, designers are allowed to “shape and ‘mold’ building elements in unprecedented detail.”

edg plans to move forward with this technique through two projects in the works. The first is a multi-family project in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, pictured in renderings [TK – above/below]. These projects will apply the same methodology but through a more contemporary lens.

“This technique allows for more textures, finishes, flowing shapes, and unique patterning which you can only get when you’re not paying for a precast form,” Meyer told AN.

To complete this and other projects, he and his team are building a customized 3-D printer suited for their size and material constraints. Furthermore, edg is planning a design competition for the potential uses of this technique on architectural facades, in part to open up the facade design process to professions beyond architecture.