In the decades following World War II, countries across the globe embarked on campaigns of residential construction, and for reasons of economy and time, many reached for an off-the-shelf, modernist solution: “Towers in the park” ringing an existing urban core. Few municipalities were as gripped by this building fever as the Greater Toronto Area, which eventually amassed the greatest number of concrete housing blocks outside of the former Eastern Bloc—nearly 2,000 altogether, with approximately one million inhabitants.

Once heralded as the solution to the housing problem, this building stock is approaching the end of its life span. The high-rises are not uniformly dilapidated, but most are energy hogs. Poor design decisions betrayed a neglect of the region’s extreme climate that, coupled with decades of deferred maintenance, left vital building systems vulnerable. Yet their apartments are enviable by today’s meager standards, and being home to so many—most recently minority and refugee groups—they cannot be easily replaced.

For architect Graeme Stewart, a principal of the Toronto firm ERA Architects, the towers are “a crucial asset within the affordable housing infrastructure of our city.”

ERA Architects has, alongside various partners, been on the front lines of saving this oft-maligned building heritage and upgrading it to Passive House standards. It founded in 2009 the Centre for Urban Growth and Renewal, a cross-disciplinary, nonprofit organization focused on improving livability and sustainability across rural, suburban, and urban environments. The Tower Renewal Partnership, a related venture dating back to the same time, is supported by a broad range of public and private sector organizations, such as the governments of both Toronto and Ontario, climate engineer Transsolar, and antipoverty foundation Maytree, among others. This latter initiative has consulted on and overseen the rehabilitation of more than 100 towers, or 21,500 units, in the region and played a critical role in developing comprehensive neighborhood planning and infill guidelines.

“We are looking at that interesting dynamic in how you assign value to an aspect of heritage [with] which many have a difficult relationship,” said Stewart. In the time since the partnership’s launch, “the discourse shifted from preserving architecture to preserving housing,” he added.

Unlike the diffuse, car-centric morphologies typical of postwar North America and especially the United States, suburban development in the Greater Toronto Area followed the European template of high-rise urban nodes linked to a metropolitan center by rail lines and ribbons of highways. These satellite cities loosely adapted Ebenezer Howard’s turn-of-the-century Garden City, only stretched vertically and less likely to maintain the requisite green belts. Peaking in the 1970s, Toronto’s building spree was partly a consequence of metropolitan regional consolidation, a decade-long process completed by 1967. But it was also impelled by robust regulation and private financing, not to mention an explosive growth in the population, which tripled from one to three million in the relevant time period. (Today, the Greater Toronto Area boasts more than six million residents.)

The towers were initially marketed to middle-class consumers, but shifting perceptions about the good life led their intended inhabitants to take up quarters in walkable and mixed-use neighborhoods. Gradually, the concrete stalks morphed into bastions for working-class immigrant and refugee communities. Yet, as happened elsewhere in high-rise suburbs, such as the banlieues of Paris, disinvestment and neglect of these peripheral communities eroded the quality-of-life expectations modern housing had raised in the first place.

The desire to reverse this arc, coupled with the immense scale of retrofitting Ontario’s postwar housing stock, has revealed priorities that overshadow the architectural, explained Ya’el Santopinto, an ERA associate who leads the center’s research initiatives. “After a half-century of use there are a range of demands on these buildings. The first is failure and deterioration; the second is adaptation to new expectations for housing quality,” she said. “Our approach is driven more by a comfort metric.”

This was especially true of ERA’s deep retrofit of the Ken Soble Tower in Hamilton, Ontario, 40 miles south of Toronto, into an affordable housing development for seniors. The project, which is expected to meet EnerPHit Passive House standards when it opens next year, is the most comprehensive in history of the Tower Renewal Partnership.

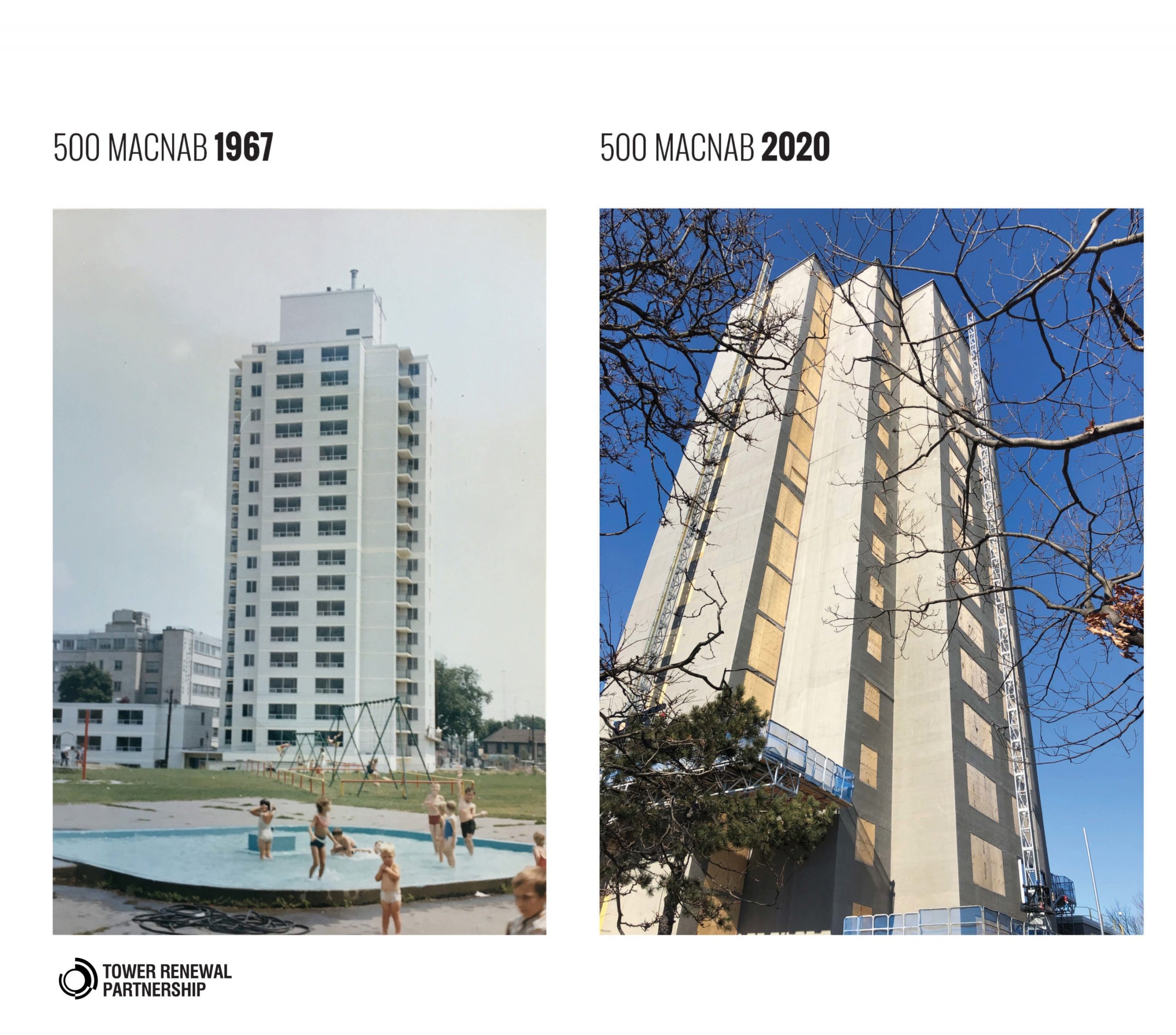

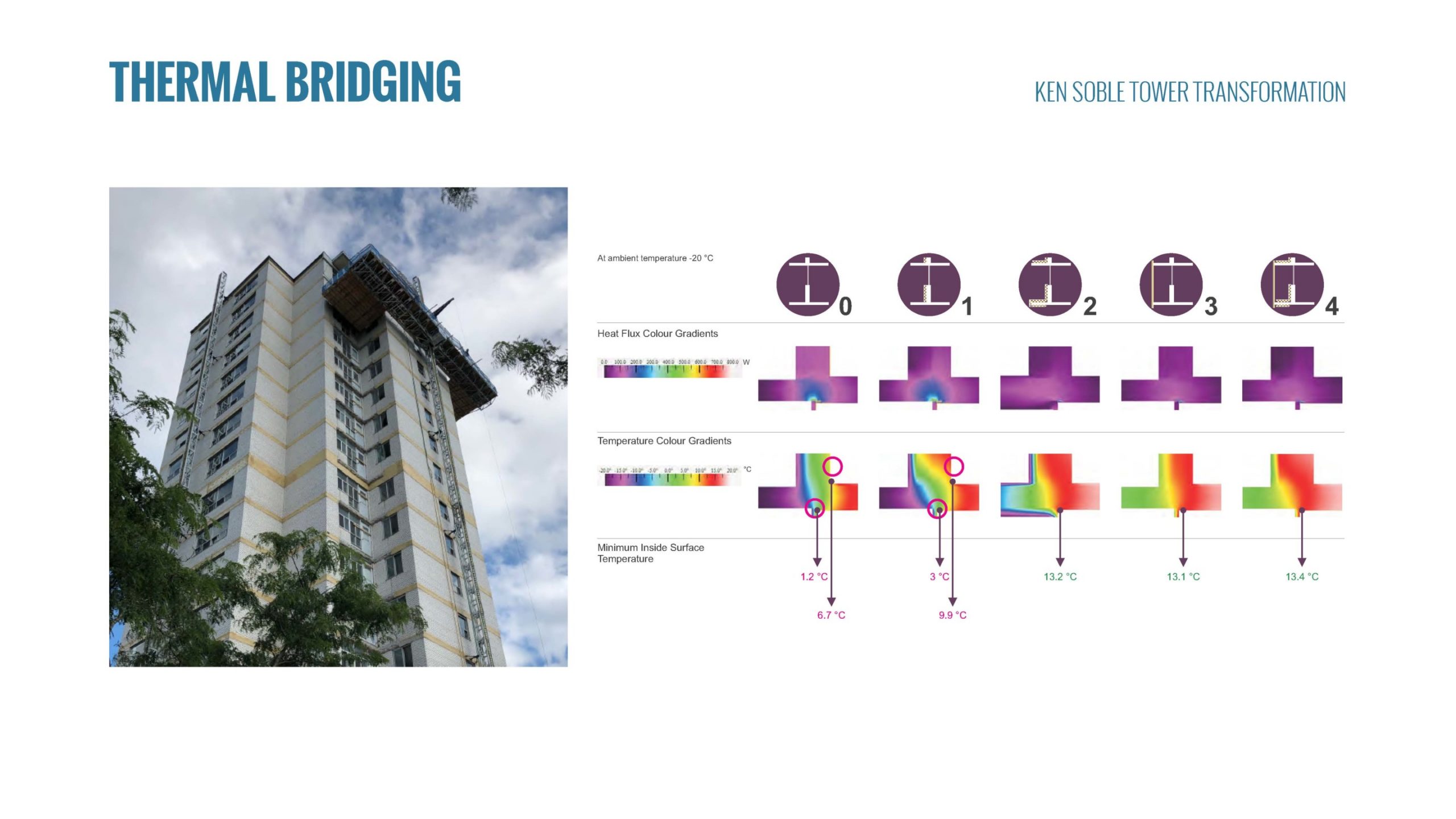

Built in 1967 on a former urban renewal site just off of Lake Ontario, the Ken Soble Tower is the oldest residential high-rise in the portfolio of the city’s housing authority, CityHousing Hamilton. The design of the 18-story tower was, to put it politely, massively flawed; for example, its uninsulated white brick facade, exposed concrete floor plates, and extruded balcony slabs, and single-glazed windows were prone to thermal bridging from the very beginning. Deferred maintenance, meanwhile, left the interior and building systems in a degraded state. In the early stages of the retrofit, the ERA team encountered significant flaws in fire barriers between units, mold infestations, and poor ventilation and ductwork.

The architects—working with the building envelope and structural engineering firm Entuitive, mechanical consultant Reinbold Engineering, and Passive House specialists from JMV Consulting—began with the exterior. They treated the existing glazed brick facade and exposed floor slab with a fluid-applied air barrier and installed a 6-inch-thick layer of mineral wool insulation. Additionally, the existing balconies were shorn off and replaced with Juliets, and all of the windows were swapped out for triple-glazed units. Modernizing the tower interior was no less complex and required the removal and replacement of mechanical and plumbing systems. ERA refurbished and expanded the HVAC ductwork, connecting it to a new centralized ventilation system. And for good measure, it lined the inner face of the perimeter wall with a 4-inch-thick layer of mineral wool insulation.

In total, project architect Santopinto estimated that the intervention will reduce the tower’s greenhouse gas emissions by a staggering 94 percent. And, importantly for the well-being of the soon-to-arrive senior residents, the refurbished units and new common areas are sufficiently insulated to remain warm or cool should the building systems fail. “We tackled this by not just aiming for today’s targets, but also at 2050 targets based off of climate data and projections three decades from now,” said Santopinto.

Unlike in previous Tower Renewal retrofits, the Ken Soble Tower was vacant throughout the overhaul, allowing the architects far greater flexibility to reinvent the building’s infrastructural core and cladding. Even if those ideal circumstances will not be present for every potential retrofit, there are still significant sustainability implications in replicating such a program across Canada. According to the Tower Renewal Partnership, there are approximately 771,000 households in the country living in degraded postwar high-rises that consume over three million tons of greenhouse gases on an annual basis. If each tower were subject to the same rigorous overhaul as the Ken Soble Tower, that figure would be cut by roughly 90 percent, to a consumption rate of 320,000 tons per year.

The affordable housing crisis and the increasingly urgent call to action against climate change are not particular to Ontario or Canada; both are conditions found in cities across the United States and the world. ERA principal Stewart noted some progress on the former front, even as he pointed to the lingering threat of political deadlock. “Housing is an entirely different issue than it was 15 years ago, and a program providing decent and good housing is now widely appreciated. At the same time as we initiated the Tower Renewal Partnership, five heritage-protected housing blocks came down. These structures are vulnerable politically.”

Indeed they are: Since the demolition of St. Louis’s Pruitt-Igoe housing projects, completed in 1976, the United States has continued to destroy and neglect this crucial asset of the country’s metropoles—many of which were constructed on the ruins of dense urban neighborhoods—leaving approximately two million residents in a state of precarious existence and worsening circumstances. The Tower Renewal Partnership provides an ambitious and inclusive road map that reappraises the social value of this disregarded but immense segment of architectural heritage and prepares it for the future.