With its first electrified underground railway constructed in 1890, London can boast the world’s oldest metropolitan transport system in the world. Snaking across the capital city, the labyrinthine network, like that of any underground system, relies on massive ventilation systems to extract warm air from below. The Bunhill 2 Energy Centre, designed by Cullinan Studio in collaboration with McGurk Architects and Toby Paterson Studio, which is located in an Underground station abandoned for almost a century, harnesses tunnel exhaust to heat surrounding homes and is shrouded with a dark red perforated aluminum screen and glazed brick.

The project is the second phase of the initial 2012 Bunhill Heat and Power Scheme and expands the prior network from approximately 800 to more than 1,350 homes, with a potential capacity of 2,200 homes. The mechanical system designed, by Danish engineering firm Ramboll, consists of a six-and-a-half-foot diameter fan located in a preexisting six-story ventilation shaft that draws warm air from the ventilation and mechanical systems that is then pushed through a heat pump which captures the heat through a closed-loop water circuit. The heated, closed-loop water circuit converts gas into a very hot liquid which subsequently runs through insulated pipes to homes within the district. In the event that the Underground system needs to be cooled down, the ventilation system can pump fresh air downwards.

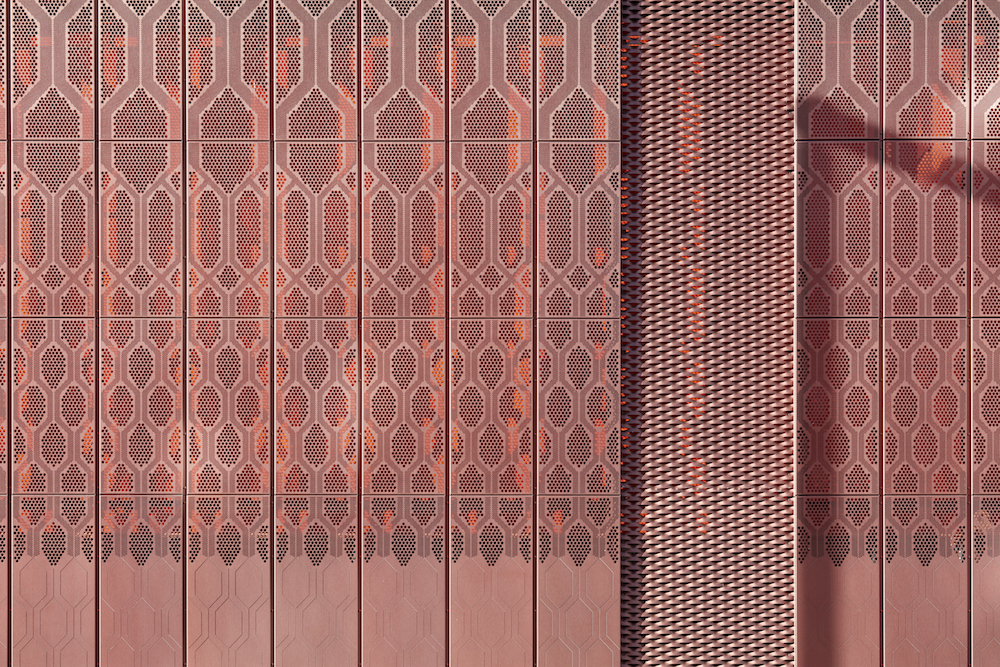

The massing and positioning of the building was informed by the plant requirements and the limitations of a tight construction site, which in turn shaped the facade panel dimensions and perforations. “We aligned the facades to the original building lines along Moreland Street and City Road and looked to increase the scale of the building at the corner by stacking the plant to give it more presence,” said Cullinan Studio partner Alex Abbey. “The corner is separated and differentiated from the flanking facades by “gills” in a different cladding texture—expanding metal mesh.”

The energy center rises from a base of glazed black brick and vitreous enamel panels, a material palette chosen for both durability against vandalism and resemblance to stations across London. The austere composition of the base is broken up by 67 interspersed cast aluminum reliefs which form something of an impression of the surrounding urban morphology. The cast aluminum panels execute Paterson’s prior research and experimentation into making visual connections between the private sphere and public realm. “I had already developed the idea of the cast aluminum relief panels being composed from ‘positive’ (formally and, hopefully, metaphorically speaking) representations of the actual plans of domestic spaces within the adjacent King Square estate and pushed this into a series of axonometric versions of these volumes.”

The pattern for the aluminum panels was developed following the massing’s configuration and is an abstract syncretism of Islamic lattice geometry and Gothic tracery. Dense at first, the pattern increases in scale and in perforations as it rises to accommodate the ventilation and airflow requirements of machinery, and, according to the design team, resembles the thermal currents coursing through the energy center. Each of the panels is approximately 18 inches wide and were detailed to be easily and fully demountable to allow for the straightforward maintenance and replacement of components, and they are held in place by a facade system of vertical mullions.

“Its form follows function; shrouding an industrial, almost alchemical process where waste hot air is converted into useful hot water for heating homes to eradicate fuel poverty and as a world first, answers the challenge of cooling the London Underground,” continued Abbey. “As a local practice, we are proud that we can contribute to the betterment of our borough and the environment of our city as a whole.”