The form of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art is suggestive and shape-shifting, not unlike the popular media to which the nascent institution is dedicated. Under construction since 2018, the curvilinear 290,000-square-foot museum is beginning to animate the entire western edge of Los Angeles’s Exposition Park, a 160-acre park opposite the University of Southern California. The project, which is named after its chief benefactor, filmmaker George Lucas, joins a loosely cohered complex of cultural and recreational destinations, including the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, the California Science Center, and the Los Angeles Coliseum.

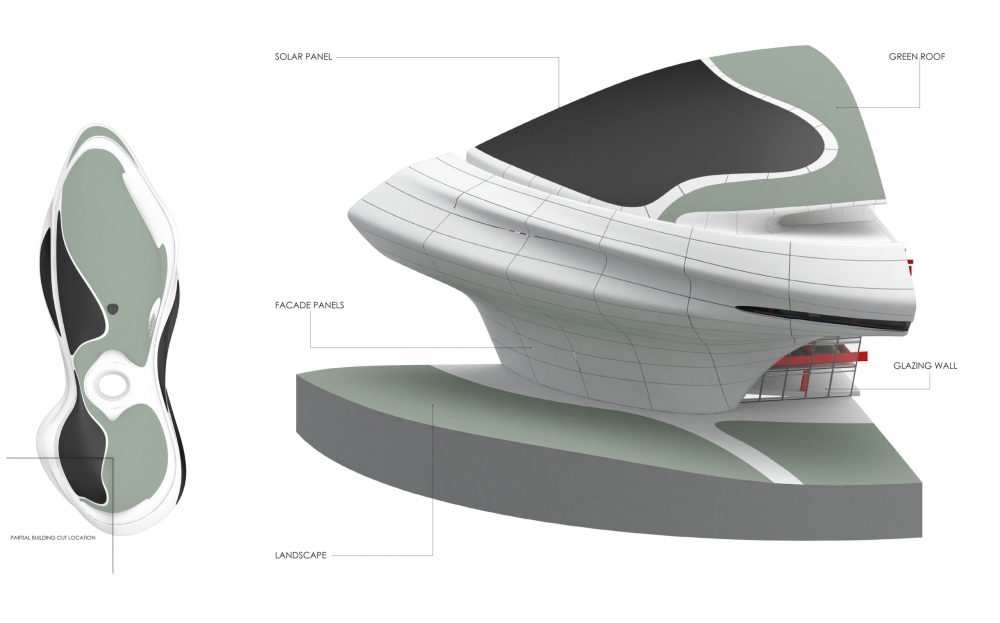

In 2014, the Beijing-based firm MAD Architects prevailed in an international design competition that tasked participants with translating the lofty, future-oriented mise-en-scène of the Lucas brand into a landmark piece of architecture. After a lawsuit prompted the museum to relocate from Chicago to Los Angeles, MAD refined its winning proposal into a stunningly amorphous “creature” with nary a right angle in sight, popularly likened to a spaceship by locals and critics alike. Containing a permanent collection and rotating exhibits dedicated to narrative art, in addition to theaters, classrooms, and a research library, the sweeping structure gracefully (in renderings, at least) spans 185 feet at its center to form a new gateway to Exposition Park.

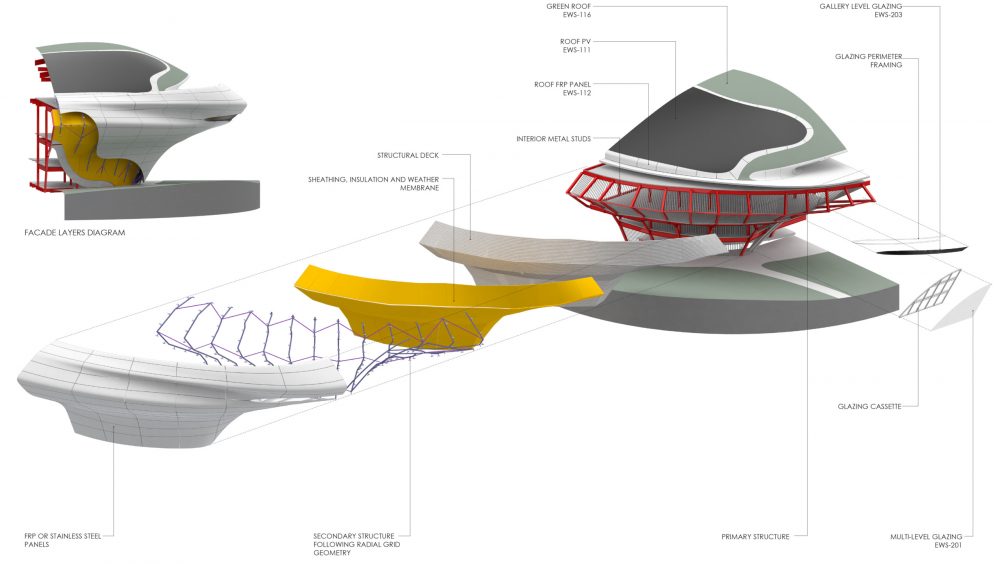

The enormous building rests on a base isolation system that will gently rock the structure in the event of an earthquake. But in order for that system to work, the design team had to be extra mindful of the weight of the outer paneling, or rainscreen. After it was discovered by the design team, which included architect-of-record Stantec and facade consultant Walter P Moore, that glass fiber reinforced concrete (GFRC), a composite material popular among architects of curvilinear building facades, would overburden the structural and base isolation system, the team opted for glass fiber–reinforced plastic (GFRP), a highly durable composite material a fraction of the weight of GFRC.

The chief benefit of both composites is the super-smooth exterior surface they can yield, provided that panels interlock in just the right way. To that end, MAD and Stantec enlisted an army of tools including Maya, Rhino, Dynamo, and Revit, each with a number of plug-ins and custom scripts. The architects sent all this modeling information over to Kreysler & Associates’ production facility on Mare Island, in Northern California, where each of the 1,500 GFRP panels is being fabricated. There, a CNC machine cuts out custom foam molds, into which a resinous mixture is injected; after the curing process, robot arms scan the panels to verify their dimensions and cut the panels to shape before honing them to a smooth finish.

The panels will then be shipped to Exposition Park, where, beginning next month, they will be installed in a secondary structure of variegated trusses branching off the burly primary structure, which is made up of predominantly straight beams. At the time of writing, the museum’s superstructure is only halfway erected, the first outlines of a cinematic vision. For now, observers of the Lucas Museum will have to fill in the gaps—or scene—themselves.