On April 19, for the afternoon keynote of The Architect’s Newspaper’s Facades+conference in New York, architect Ian Ritchie discussed his decades-long involvement in forward-looking glass architecture. Beginning with the tongue-in-cheek statement, “Glass is the answer; what was the question?” the British architect detailed the technological specifications and design considerations behind his projects. Ranging in size from personal residences to convention centers, the projects convey his expertise with manufactured materials.

As head of his own practice, Ian Ritchie Architects, Ritchie’s process is influenced by a range of fields, from neuroscience to poetry.

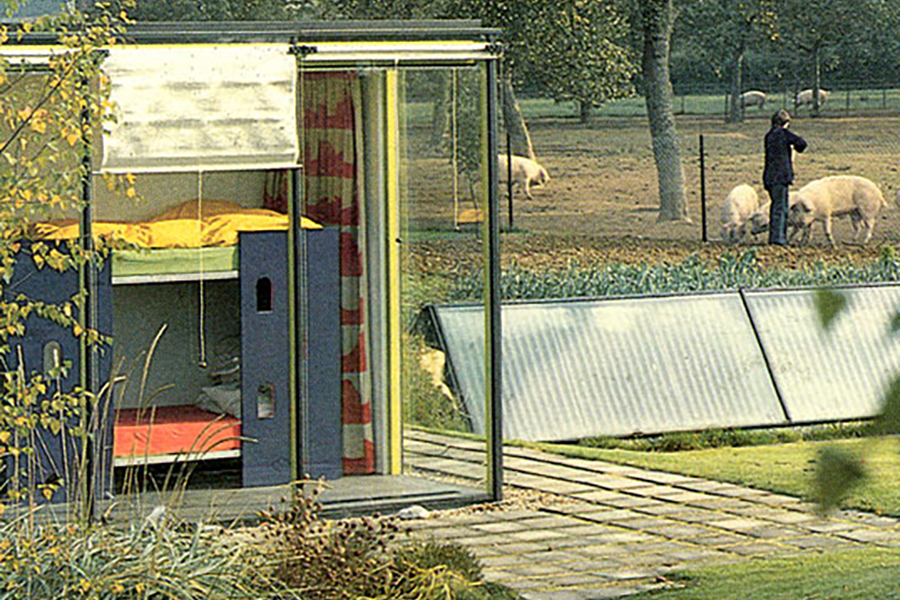

Ritchie began with one of his earliest projects, the self-constructed Fluy House (1976). Composed of a prefabricated set of materials, including a lightweight steel frame and pre-cast concrete floor slabs, Ritchie described his early curtain wall as “glass acting as a windbreaker,” a thin protective barrier between shelter and the site’s surrounding countryside.

Ritchie also described projects he worked on as a founding partner of the engineering firm, RFR Engineers. For example, he talked about unique projects such as engineering I.M Pei’s Louvre Pyramids, which entailed the creation of a full-scale Kevlar mockup and the use of “phantom fixing” to insure the transparency of the glass structure’s final design.

Next, in talking about the design of Reina Sofia Museum of Modern Art’s circulation towers and the Messe-Leipzig Glass Hall, Ritchie described how unique engineering devices such as externally suspended and grid-worked glass panels bring the tectonics of design and engineering into public view while creating open and accessible spaces.

In line with his firm’s straightforward forms, Ritchie was critical of the contemporary trend of hyper-engineered glass facades with multiple curves and contortions, asking, “Is architecture intelligence or indulgence?” Instead, he emphasized the natural, biological forms that influence his creative process and, ultimately, his firm’s output.

Ritchie’s drive to bridge the highly technical, manufactured character of glass with natural objects and processes was also highlighted by his presentation of the firm’s recently completed, 150,000-square-foot Sainsbury Wellcome Center.

Located in London’s Fitzrovia, a central city district surrounded by architectural conservation areas predominantly comprised of Georgian architecture, Ritchie saw the Sainsbury Wellcome Center as a “melting ice block spilling into the surrounding neighborhood.” To fulfill this analogy, the firm opted for translucent cast glass with vertical, corduroy-like detailing that imitated the stone rustication and brick-and-mortar facades of the surrounding area.

Ritchie concluded with a call for architects to recognize that current glass design and architecture may be surpassing contemporary engineering capabilities. In his view, too many architects are acting as sculptors, an approach that will fail to “make glass warm and haptically friendly” to the public.