Facadism, the act of retaining a historic facade whilst fundamentally adapting a structure’s interior, is often maligned by preservationists as relegating historic architecture to urban set pieces. Lost in such orthodox pedagogy is recognition of the functional demands of the client and the pragmatic reality that buildings evolve over time. Kliment Halsband Architects (KHA), a New York-based firm with particular expertise in historic preservation and adaptive reuse projects, recently completed an inventive renovation and expansion for the Friends Seminary school which included the insertion of an academic core between a meticulously restored Italianate street front and a courtyard-facing elevation of zinc and brick.

Friends Seminary was founded in 1780 and is located on the border of Gramercy Park and the East Village in Manhattan. Over the centuries, the school gradually expanded to encompass a fairly significant campus adjacent to Stuyvesant Square Park; that includes three Italianate homes built in the mid-19th century and purchased in 2014, and the 1960s-era Hunter Hall. However, this growth lacked an overall cohesive master plan, with floors across the campus misaligned and not in compliance with contemporary ADA standards. For KHA the primary challenge of such a project was to develop an intervention that successfully respected the existing historic fabric while creating programmatic space invisible from the street.

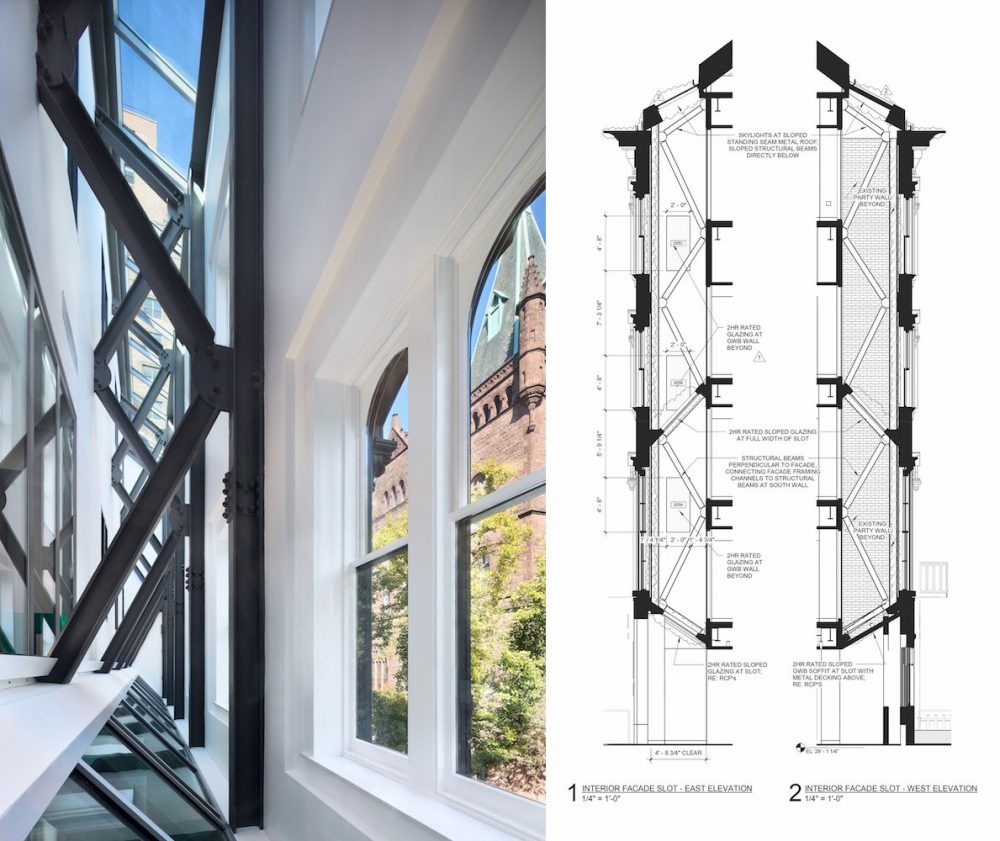

The project began with the construction of two additional stories atop Hunter Hall, which accommodated for lost classroom space during the renovation process. Collaboration with structural engineer Silman was key to this project, and the complexity of the demolition and reconstruction was truly daunting. The new 76,500-square-foot building is offset approximately five-feet from the existing historic facade and houses the bulk of a lateral support system bridging floors across to Hunter Hall. An extensive temporary bracing system for the facades had to be installed and maintained throughout the buildout of the structure. A steel moment-and-brace system was inserted between the historic facade and new building as the project neared completion, and the result is a captivating five-story light well that highlights the utilitarian poetics of structural engineering.

“Through this approach, we enable the building’s history to continue into the future,” said KHA founder Frances Halsband. “By exposing the steel structure, we reveal the key design tool used to bridge the old and the new making it an educational experience for the school community who use the building daily.”

KHA worked closely with the Landmarks Preservation Commission and local preservation groups to ensure that the facade restoration was in keeping with the Stuyvesant Park Historic District and the facade restoration occurred over the course of one year out of the overall three-year construction schedule. Restoration work, led by Jablonski Building Conservation and Northern Bay Contractors, entailed the repointing and replacement of brick; the restoration of terra-cotta eyebrow lintels; the faithful replication of historic wood windows, and the repair of the ornately-carved wood cornice.

The courtyard elevations are a demonstration in contextually sensitive infill and deft maximization of occupiable area allowed under zoning. In a series of setbacks and bay-like projections the expansion unfolds onto terrace and courtyard, and is clad in limestone-colored brick and vertically-seamed zinc panels. “The zinc was selected for its light to medium value and warm neutral coloration to minimize the massing of the new additions on the adjacent buildings facing the courtyard and from the roof terrace atop the rear yard enlargement allowed by zoning for community use,” continued Halsband. “Our approach was to design these elevations with new materials distinct from while sympathetic to their surrounding existing building fabric.”