From October 25 to October 26, The Architect’s Newspaper is hosting its Facades+ conference in Los Angeles for the fourth year in a row. The conference features leading architects based in Los Angeles, including Heather Roberge, Principal and Founder of Murmur Architects; Tammy Jow, Associate Director of AC Martin; Thom Mayne, Founding Principal of Morphosis Architects; and Stan Su, Director of Enclosure Design at Morphosis Architects. To learn more about what Morphosis is up to, emerging facade technology, and wider industry trends, AN sat down with Thom Mayne in the firm’s New York office.

The Architect’s Newspaper: When did you start getting interested in façade innovation, and what do you find most interesting about it today?

Thom Mayne: It started in the early 2000s; we were working on a project in Seoul, on the Sun Tower. We were investigating the possibility of a second skin, an artifact that was much more connected to an aesthetic formal exercise because it freed us of the norm of a window curtain wall and the whole notion of facade. We had continuous surface and that allowed us a lot of freedom in a completely different direction.

After that, we were working on the Caltrans project in Los Angeles and the General Services Administration (GSA) project in San Francisco. Both were very distinct projects that required real thinking on performance, using facade openings and scrim walls to take advantage of natural light and exterior temperature conditions. The whole thing became a huge exercise in environmental performance. We saw it as part of our responsibility to represent architecture within a state-of-the-art context in terms of its use of energy.

It is not something we’re focused on, but there’s nothing that comes out of the office that doesn’t require some level of environmental facade performance.

When we opened the GSA building, Nancy Pelosi was there and she didn’t like it. She likes Victorian architecture, and I said, “Nancy, actually this is how it works, and you have to understand its performance,” knowing that she’d agree that our values are parallel. In fact that’s interesting too, that the average person relates to a building just in terms of its appearance. It’s fairly straightforward. In reality, the skins had to do with weight and their ability to move and their technological performances. It wasn’t about the metal; we didn’t start it by wanting to do a metal building. It’s a result.

In terms of the metals, I think the Bloomberg Center at Cornell Tech was quite successful. We’re experimenting with textures and imprints on metal, and in that case, it resulted in a set of random pieces and it looks like it’s dynamic, in a perpetual state of movement based on the reflection of the sun. The facade’s 500,000 perforations are stationary, but if it looks like its moving, it’s moving. We used metal skins at Cornell Tech, but we are sort of done with the whole metal thing; we want to move on since people link us with metal buildings.

What are you working on and what do you think we’ll see in five years?

TM: We are pursuing a couple other projects making the skin active and literally dynamic, which presents another set of possibilities. It just keeps changing the whole notion of facade. A large segment of the profession today is recognizing completely new opportunities.

We really pushed environmental performance with our recent work, the Kolon One & Only Tower [in South Korea]. It’s a state-of-the-art research and development center with a sophisticated west-facing fiber screen wall. We found much more aggressive subcontractors in Korea and China. Here [in the United States] they just think, “Haven’t done it, can’t do it.”

Outside of the United States, contractors and clients are more willing to experiment with new materials and techniques?

TM: It is really weird as we’re still the wealthiest economy in the world; we’re in a place that’s affecting architects for sure, but creating very timid architecture. You’re staying competitive if you are creating intellectual capital.

We couldn’t have done it in the States or for an American client; it would’ve been too aggressive or too risky on their end. [The Kolon tower] was very much moving the ball forward just advancing kind of this notion. Again, it’s this one single element, the exterior wrapper that you see in the work.

Unlike other projects, we never set out to make a stainless steel building, even though it withstands weather and it’ll be around in 100 years. The response [for Kolon] was to various performance demands. What it does is allow a completely different reading of the work because you get singularity of the surface.

What facade and construction innovations do you think we’ll see in the forthcoming years?

TM: Without question, there’ll be a continuation of technologies that produce more efficient envelopes. New materials and increased performance characteristics will drive a lot of it. Design becomes less of a focus of your work.

I would also question the question. I think today, there isn’t a lot of attention to the future since it’s hard enough to grasp the present. The whole idea of the future is also that it is kind of unknown. And the answer is, I don’t know.

At Cornell Tech’s Bloomberg Center, we were discussing where they are going with the program, and they responded, “We don’t know; we are going to put a biologist, a poet, and a mathematician together and invent projects.” And you go and talk to Google’s design group and ask what they are doing? Same thing, “I don’t know.” We are going to put certain people together and find something interesting. There’s more of that process going on and it makes sense; continued thinking and progressions in material and integration.

Construction techniques and the ways we build other large complex objects, such as automobiles, are open to significant investigation. Advances in prefabrication allow for the efficient mass production of “handmade” pieces and the continual reworking of materials.

For certain contemporary projects, like Kolon One & Only Tower, to get the desired form, shaping, and performance of the facade components, metal is no longer as useful due to its heavy weight. That [investigation beyond metal cladding] is definitely going to continue as we expand our material language.

As you work on certain projects within the studio, they take on their own life. So I already know we’re interested in pursuing that again with a similar material and technology because it’s going someplace that we couldn’t in other work. It’s giving us a very different look and a different direction at the same time. It’s opening up coloration and a different palette, because we wore out metal. We have to say, “After number six or seven, let’s move forward.” We’re doing it differently because we have to do it differently. It’s not that we couldn’t continue to do it in perpetuity, they’re actually operational. It’s more a desire for something new.

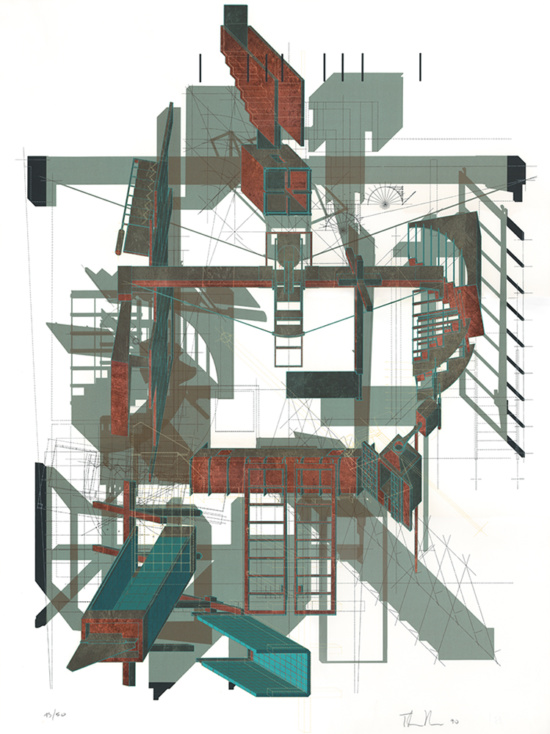

You founded Morphosis in 1972 as an interdisciplinary practice. How have the firm’s artistic tangents informed your design projects?

TM: As part of the visual culture, drawings, paintings, sculptures, objects of all types, including furniture, all share many types of connections in the design world and in their formal structures, and they’re, to me, singular. The artistic tangents are dealing with organizational ideas, compositional ideas that feed directly into the work.

If you can look at a lot of [our tangent projects], you’re going to be able to see absolute connections between organizational strategy and material connections. It’s all part of a visual world that interconnects—the drawings and the abstract work become precursors to the work itself, that is, the architecture. The different mediums allow you to explore different formal ideas free of contingency. It’s free of the pragmatic forces whether it be functionalities or economics. It allows you to explore it as a pure idea, which is useful mentally.

You need the freedom to explore ideas in a much purer kind of framework outside of contingency, because if there’s anything difficult in architecture, it’s the limits that restrain a certain amount of freedom necessary to explore an idea. But I would say on the other hand, those same limits are what architecture is about and are useful. It’s a balance between constraint that gives you clear focus on a problem and other constraints which are just annoying or which are just limiting.

Going back to our earlier discussion of where even certain things can take place, like we discussed with Kolon in Korea, I just need an environment that’s a little freer and open to just explore ideas. It’s a constraint I need to remove. This other artistic work is just to think freely, but those ideas absolutely find their way into the work. They’re absolutely interconnected. When I come back to my office this artwork is abstract urban design and the strategies of urban thinking.

Further information regarding Facades+ LA can be found here.