Located in the University of Michigan’s Ann Arbor campus, the Biological Science Building is a dual-purpose building housing both a biological science program and a museum of natural history. The nearly 300,000-square-foot building, designed by Ennead Architects, was constructed in two phases—the academic spaces opened in 2018 and the museum in 2019—and enclosed with a corrugated terra-cotta rain screen and brise-soleil.

The core of the Ann Arbor campus is composed of a dozen halls and auditoriums designed by the renowned Detroit-based industrial and commercial style architect Albert Kahn. His work on the campus, exemplified by buildings such as Hill Auditorium and the Harlan Hatcher Library, is primarily Renaissance Revival and built of reddish-brown brick and terra-cotta with slight ornament found at the cornice and string course.

For Ennead Architects, the setting was a point of reference to be respected and, to some degree, emulated by any contemporary intervention. “We used deep corrugations and textures of the terra-cotta facade to break down the sale of the laboratory building to relate it to the campus environment,” said Ennead design partner Todd Schliemann and associate partner Jarrett Pelletier. “We were interested in using the depth of the corrugations, in a play of light and shadow, to create a facade that was variegated, reinterpreting the Albert Kahn historic brick buildings on campus which are rich in variegations of color and texture.”

The three box-like volumes of the Biological Sciences Building cantilever off of a one-story podium and are linked at the hips by full building height atriums with oversized glazing bays. Produced by manufacturer Shildan Group, the terra-cotta tiles are treated with a standard matte finish and arranged in three formats; flat, combed and honed. Through the terra-cotta tiles shifting orientations—all are five-and-a-half inches deep—the facade is cast in an ever-changing condition of light and shadow which suggests the illusion of varied finishes for the panels.

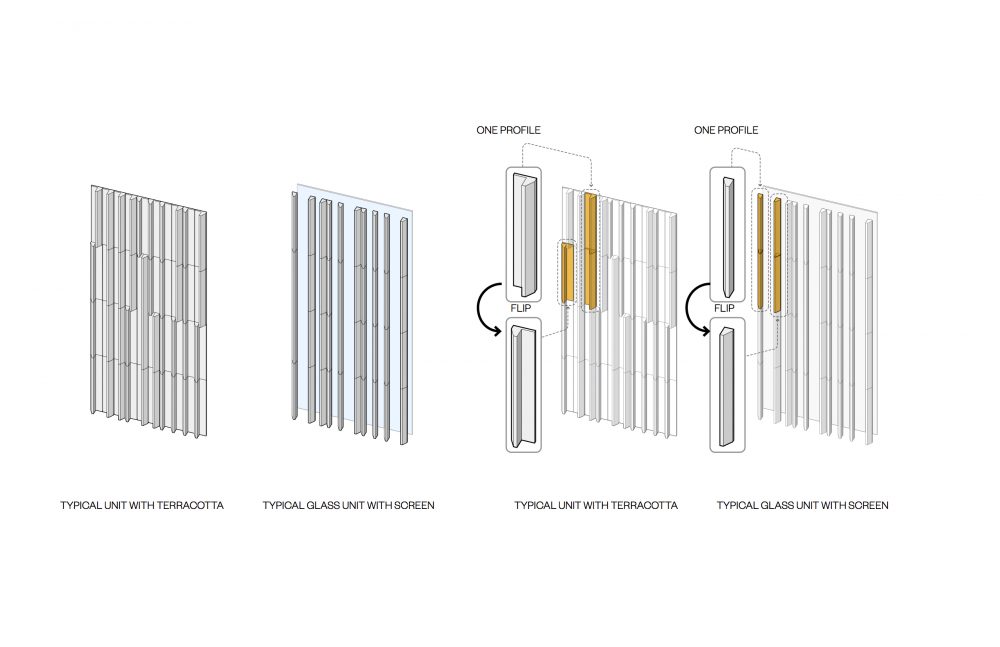

Considering the varied internal functions across the project, the design “The patterns of glazing and opaque elements was designed to maximize daylight in spaces where people spend much of their time and temper it in spaces that house research equipment,” continued Schliemann and Pelletier. “Our design-team utilized parametric modeling to create a facade that looks infinitely custom yet is actually made of repetitive modules.

Curtain wall modules span between 16 and 20 feet from floor to floor, and are held by aluminum framing supporting the weight of both glazing and terra-cotta. Throughout the facade, the terra-cotta tiles also function as screening elements at several points. Offset from the glazing, the tiles are threaded to the unitized curtain wall’s stack joints with a series of steel tubes, and, for extra-tall units, steel tie-back elements handle the increased lateral loads.