Houston is a city of contrasts where, because of a dearth of zoning codes, shimmering high-rises dwarf anonymous strip malls and suburban bungalows abut oil refineries. Sandwiched between the Rice University campus, Hermann Park, and a tangle of highways, the Museum District is no less idiosyncratic, even if it is more high-brow in its aspect.

The district itself offers a constellation of high-profile works from big-name architects, including Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Rafael Moneo, and Lake|Flato at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH) alone. Joining this eclectic bunch at the MFAH is the Nancy and Rich Kinder Building, a 200,000-square-foot museum expansion housing a growing collection of 20th and 21st-century art. Designed by Steven Holl Architects (SHA), the Kinder Building advances a novel solution to age-old problems in this corner of coastal Texas—stifling heat and intense daylight.

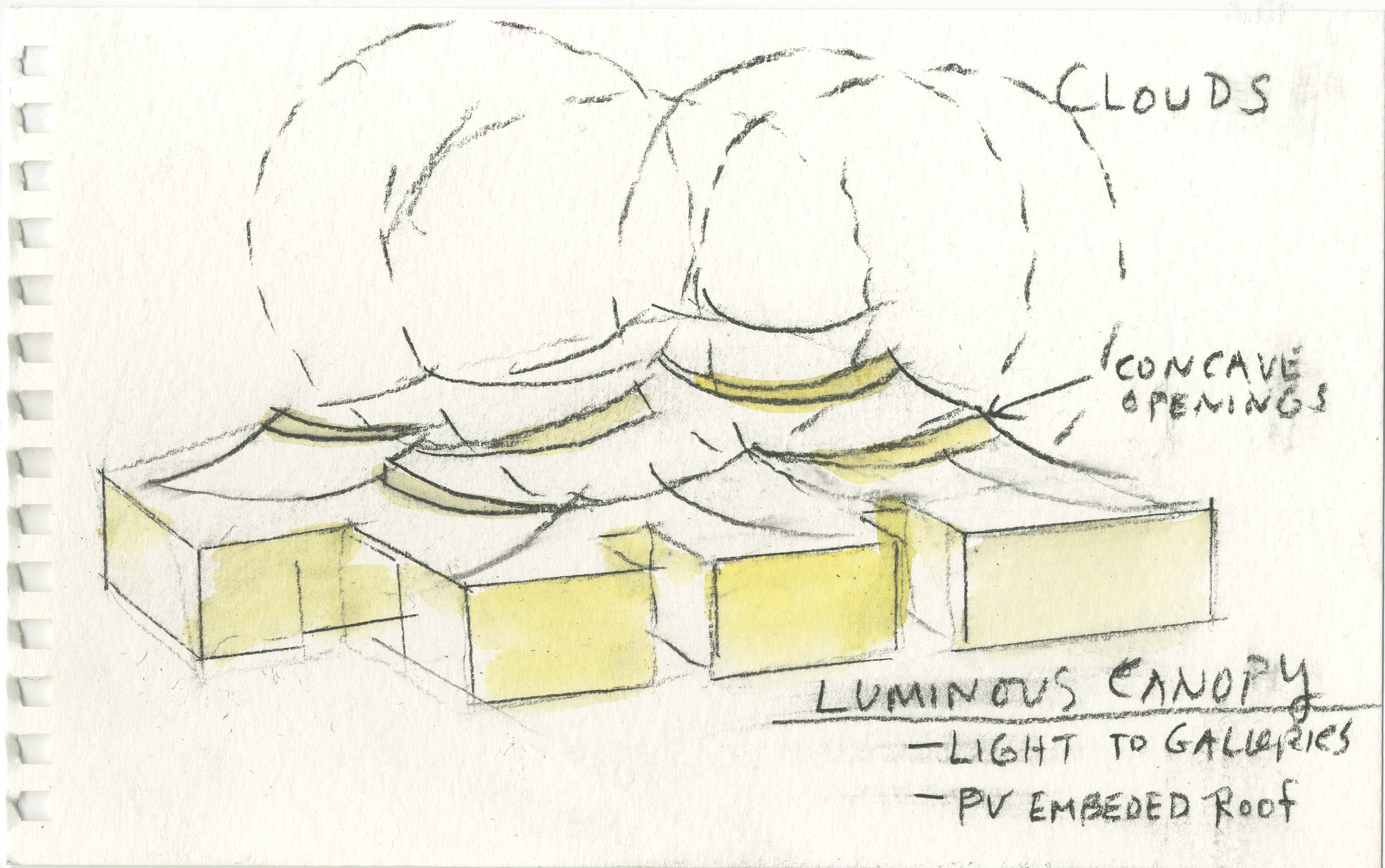

Rising on a trapezoidal site, the new wing is a bulwark of light-gray structural concrete and milky concave glass. Seven forecourts—“porous gardens,” per the architects—chip away at the considerable massing, providing much-needed shade at perimeter entry points. The buoyant roofline further leavens the massing and strategically guides natural and diffused light through clerestories into gallery spaces and corridors inside.

“Concave curves, imagined from [tracing] cloud circles, push down on the roof geometry, allowing natural light to slip in with precise measure and quality—perfect for top-lit galleries, and “shape the gallery spaces organically in a unique, rather than mechanical and repetitive, way,” said SHA senior partner Chris McVoy.

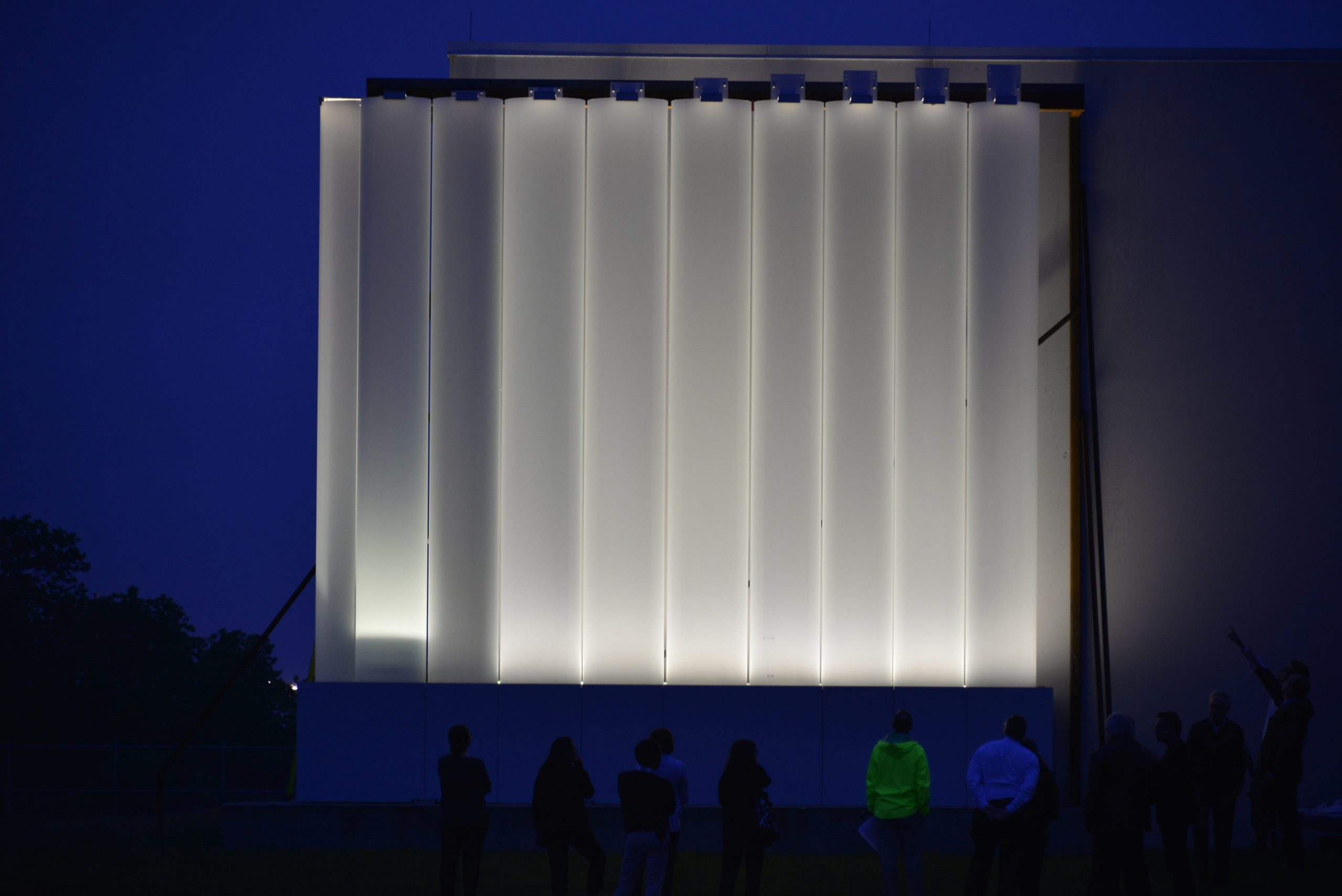

The control—or, perhaps, harnessing—of natural phenomena is taken a step further on the building elevations, which are each draped in a semiopaque glass veil. These vitreous screens couple conditions of translucency with depth, and an ambiguous materiality that bridges Mies’s dark and trim Brown Pavilion and Moneo’s tough-as-stone Audrey Jones Beck Building. In total, more than 1,000 bent glass pieces are affixed to the Kinder Building, and they come in approximately 450 different sizes—the largest of which reaches a height of nearly 20 feet and spans a width of approximately two and a half feet, with a bending radius of just over a foot.

Early facade prototypes originated in SHA’s fabrication workshop as vinyl and half-translucent acrylic tubes, which pointed to the lamp-like glow and arcing light patterns that glazed cylindrical tubes could achieve. Climate engineer Transsolar was brought on to investigate the ecological implications and potentials of SHA’s design concept. In maintaining a 5-to-40 percent transparency through acid-etched PVB laminate, the facade effectively reflects solar gain away from the primary concrete structure. Meanwhile, the multi-foot cavity separating the glass and the outer edge of the building promotes natural convection, guiding heat up toward the roofline.

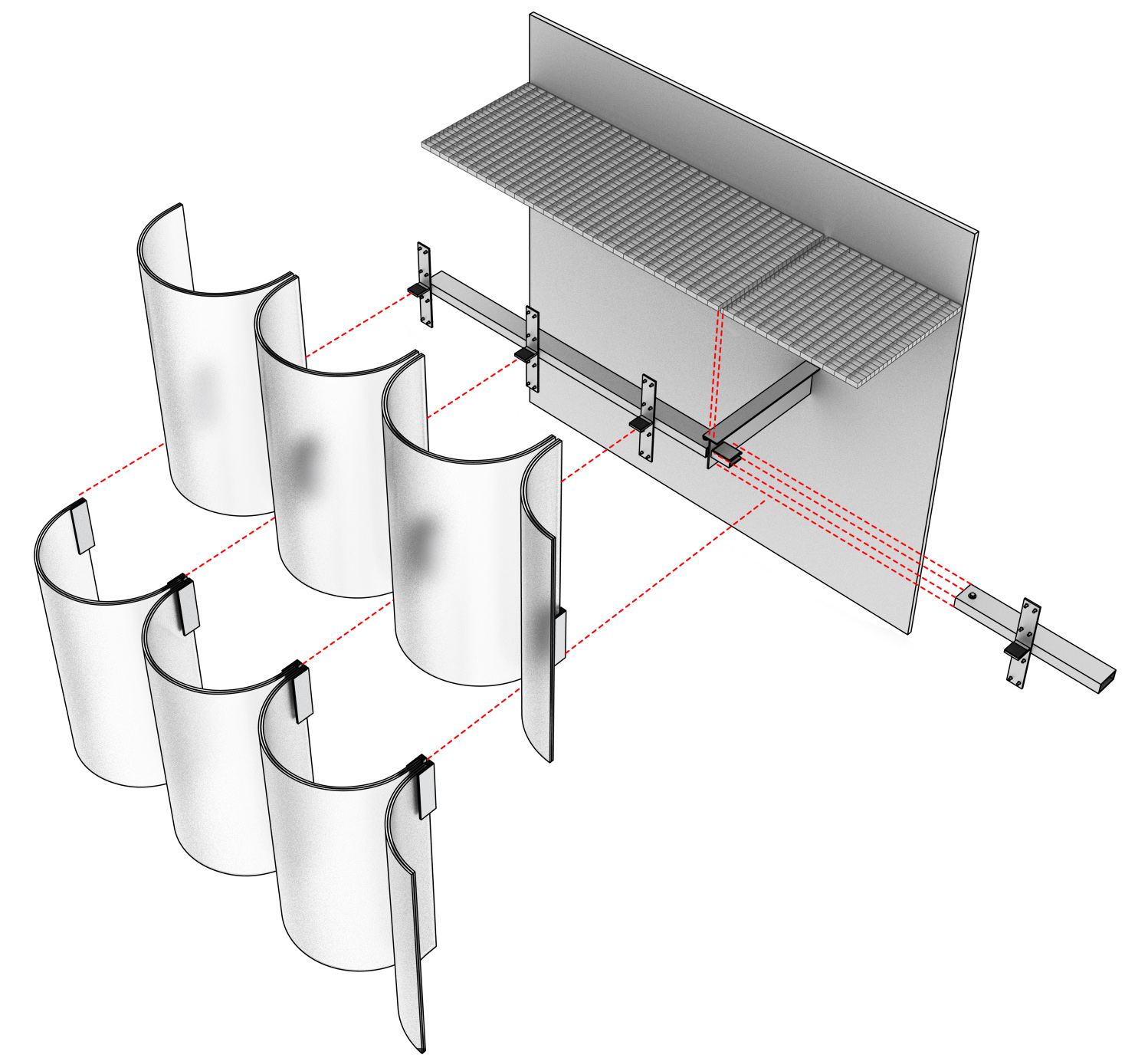

Scaling up the prototypes required resolving difficult details, including where the tubular geometry meets the 90-degree corners of the building. SHA relied on facade engineer Knippers Helbig Advanced Engineering and facade systems producer and installer Permasteelisa Gartner. The architects also closely monitored the fabrication of the tubes themselves, which was no mean feat—it took Shennanyi Glass up to eight hours to individually sculpt and subsequently cool each glass panel. SHA would shuttle back and forth from New York to Shennanyi Glass’s plant in Shenzhen, China, and later to Gartner’s facilities in southern Bavaria, Germany, to survey full-scale mock-ups prior to their shipment to Houston.

Once on-site, the tubes were affixed to the outer walls of the concrete structure by way of an ingenious system of steel tube outriggers spaced at intervals of nearly 8 feet. “The glass tubes themselves rest on small stainless-steel shelves for dead load support while the lateral support consists of four aluminum clips (one in each corner), siliconed to the back of the glass. The length of these clips varies with glass height and wind exposure,” explained SHA senior associate Olaf Schmidt.

The semicircular glass tubes appear to hover above the primary volume, and in their luminescence and stepped castellation at the roofline recall the visual effects of Gio Ponti’s Denver Art Museum. While the facade reflects ever-changing daylight and seasonal weather conditions, it remains dappled with shadows from the muscular branches and dense foliage of decades-old Southern live oaks lining the abutting streets.