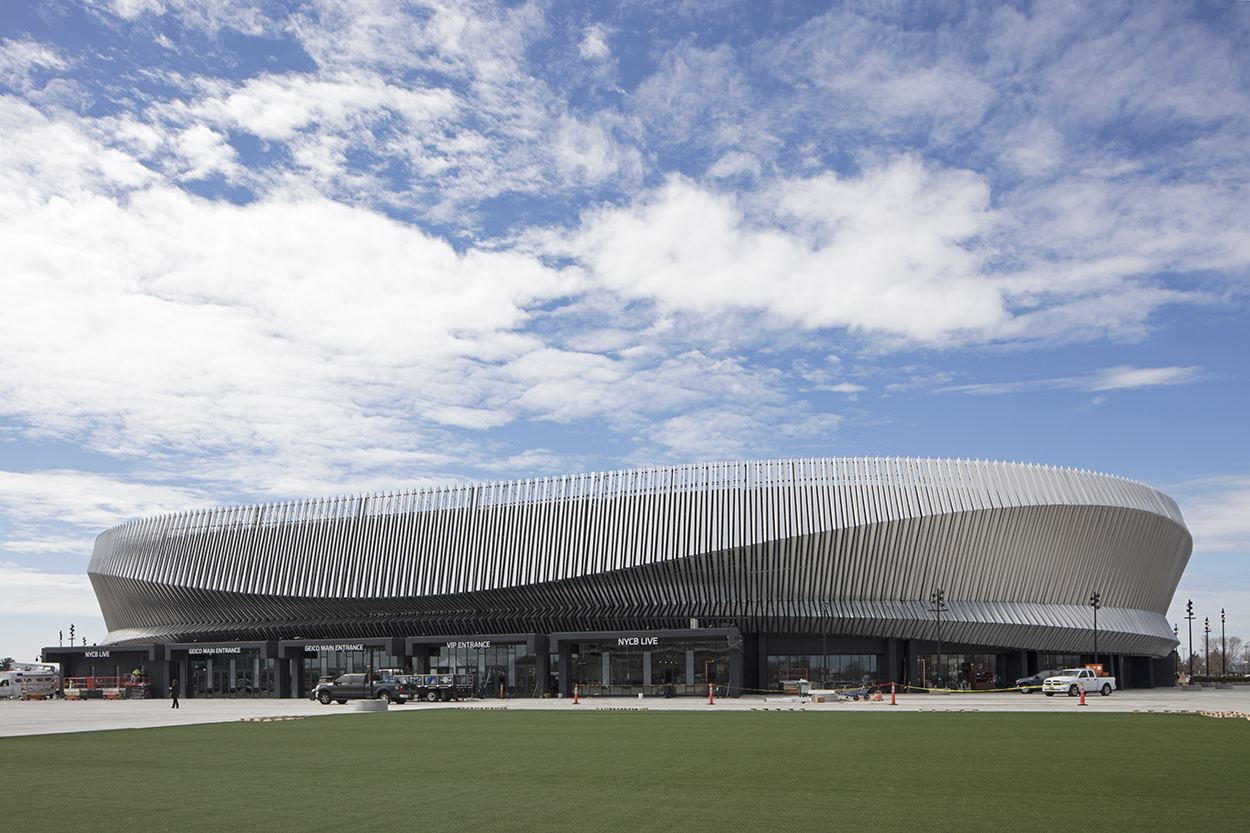

Originally opened in 1972, the old Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum on New York’s Long Island was given a facelift and interior renovation by SHoP and Gensler respectively in 2015.

SHoP’s team relied on the concrete massing of the 1970s structure to shape a new facade composed of over 4,700 brushed aluminum fins that wrap the building in broad sweeping curves. The project, which benefitted from a rigorous digitally-conceived workflow, delivered the new undulating facade geometry by precisely varying each of the fins in profile and dimension. Two primary fin shapes are designed from one sheet of aluminum composite material (ACM), minimizing waste while highlighting SHoP’s commitment to a design process that is tightly integrated with fabrication and assembly processes.

John Cicerone, partner at SHoP, told AN that one of the successes of the project is the new facade’s reflective effects that pick up on colors of the surrounding landscape. This is especially evident during sporting events where crowds wearing the home team’s colors reflect onto the facade.

The project in many ways mirrors SHoP’s success with Barclays Center over five years ago—same client, same building type, similar design process. When asked what, in this project, arose as a surprise or a challenge to the design team working on Nassau, Cicerone candidly said, “Nothing!”

He elaborated, “As we continue these projects, it’s a continuous iteration: We recycle process. I don’t think this industry does enough of that.”

“Don’t ignore fabrication constraints and input from contractors,” Cicerone said.

The fins are planar and negotiate a ruled digital surface, which was informed by early feedback from fabricators and contractors.

“An intelligence builds from doing other projects like this. While the componentry and hardware differ, the actual process of how you structure the model and develop methods of automation improves with experience.” The architects cite simple definitions which they adopted and advanced from prior projects which help to automate the generation of parts for geometrically complex assemblies. “This to us was a proof. It’s a great testament to not being surprised by the process,” Cicerone said.

The design process for SHoP was initiated with a laser scan of the existing arena, resulting in a highly detailed topographic mesh surface that became the base geometry for forthcoming design and fabrication models. The framework of the new skin was designed as a long-span space frame, springing off massive existing concrete piers that were, in the words of Cicerone, impressively over-structured. The resulting structural subframe was assembled on the plaza level of the stadium and craned into place. Only 32 “mega-panels” were required.

“Facades are the closest you can get to manufacturing in architecture,” Cicerone said, “but we are looking towards using this process throughout the building. How can it inform the superstructure and the interior? We are working to scale this process up.”