A veritable spaceship has landed on the outskirts of the Botswanan capital city of Gaborone, its coppery carapace glinting in the unrelenting sun. This is the Botswana Innovation Hub, and while its form evokes the stylings of Battlestar Galactica, it is very much of this world.

SHoP Architects was awarded the project in 2010 following an international competition, the result of an earlier directive by the Botswanan government to transition its economy from natural resources to intellectual capital and services. In addition to holding symbolic power for the nation, the Hub represents the culmination of SHoP’s research and practice in fully automated direct-to-fabrication and project-tracking techniques largely initiated at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn a decade ago. The approximately 270,000-square-foot complex, which broke ground in 2014 and is due to open next year, seems to hug the contours of the southern African veld. Three low-slung volumes, interlinked at multiple points, are clad with projecting bronze-colored anodized aluminum panels. Slender ribbons of silver-coated window walls course between, and are shaded by, these aluminum canopies. The facility incorporates both passive and active building systems, in addition to landscaping at both the roof canopy and ground-level—strategies that have made it Botswana’s first LEED-certified project.

Since its founding in 1996, SHoP has consistently pushed for the integration of automotive and aerospace engineering techniques, spanning from micro to macro scales, into the architectural design process. Central to this approach is the use of 3D design and engineering software, such as Dassault Systèmes’ 3DEXPERIENCE platform, to generate a comprehensive digital library of components customizable to individual projects. For John Cerone, SHoP principal and director of virtual design and construction, the use of such tools facilitates “projects as portfolios of processes from macro massing down to the component level—traceable and trackable in real time from design, fabrication, transport, and installation.”

Although the upfront investment in such a computationally intensive methodology is significant, the payoff, suggested Cerone, lies in the relatively seamless transfer of detailed information to both the manufacturer and the contractor. After design work was completed, SHoP exported a digital sample of a facade panel to project bidders, who then fabricated prototypes while inputting their own recommendations in accordance with the digital model’s guidelines. The fabrication contract was ultimately awarded to the South Africa–based fabricator and installer World of Windows. With digital guidelines in hand, local partners were able to manage the bulk of the work on-site, requiring little physical oversight from SHoP’s team. (The New York firm maintained a tight crew of five on-site, as well, first in South Africa, then in Botswana.)

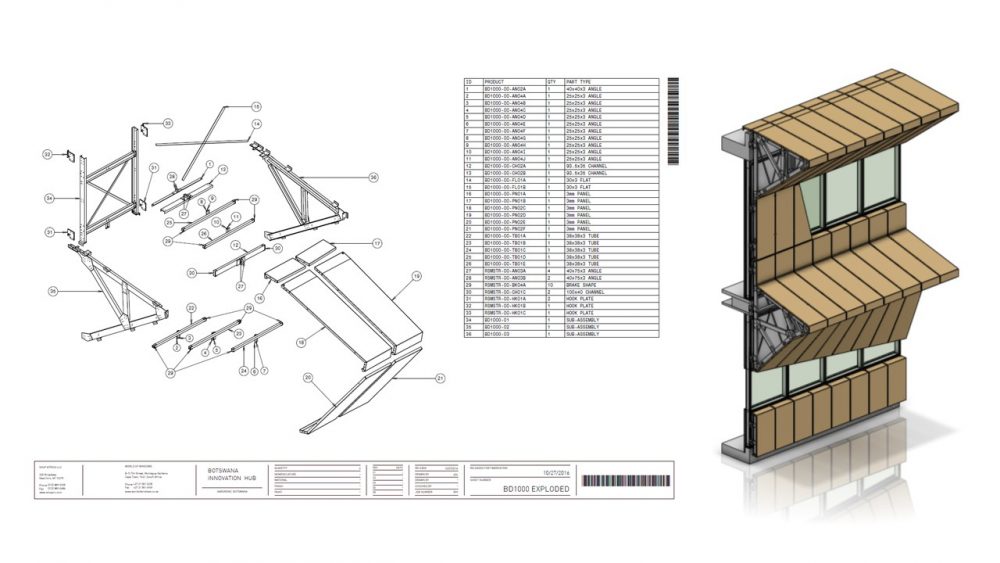

It is important to recognize the sheer complexity of the facade system. There are 3,000 panel units with 1,700 unique panel types; all are approximately 4′ wide and reach depths of 6′, 6″ and heights of 14 feet. The units are divided into 60 separate “families” or templates, each containing 500 similar panel types. In total, approximately one-million parts make up the enclosure composition. The panel substructures are fixed, via a series of integrated clips, at the window wall or at the slab edge of the structural wall or steel canopy.

Following fabrication in Cape Town, South Africa, the panels were shipped approximately 900 miles north to the project site, where, in the parking garage beneath the Botswana Innovation Hub structure, the general contractor and facade installer oversaw their final assembly. Each of the prepackaged panels arrived with detailed step-by-step instructions in the form of axonometric diagrams—think IKEA, only without the difficult-to-pronounce Swedish nouns.

During installation, the facade components were tracked in real-time and digitally scanned for comparison with a cloud-based digital “twin.” The technique allows for the immediate identification of dissimilarities—resulting from either incorrect installation or other miscalculations—and their equally immediate resolution through on-site adjustment.

What are the industry implications for this technology-heavy approach to design and construction? For SHoP founding principals Christopher and William Sharples, the objective is to reestablish the relationship between designer and builder, harking back to the tradition of master masons or the syncretism of architecture and industry advocated by the Bauhaus. They added that projects and their fabrication effectively function as white papers to be challenged and built upon through ongoing feedback and collaboration. At the Innovation Hub, this productive exchange was limited to one architecture component—the enclosure system—but the firm hopes to expand it across all phases of construction. It’s a development, said the Sharpleses, that would significantly reduce waste associated with construction and even deter exploitative labor practices.