Though it’s been open for less than a year, One Hundred, a 36-story residential tower in St. Louis’s Central West End neighborhood, carries itself like a city landmark. Designed by celebrated Chicago architecture firm Studio Gang, the building peacocks along Kings-highway Boulevard, its tiered, faceted profile evoking a giant crystalline headdress.

There are echoes of the art deco stylings of the nearby Park Plaza Tower, and in the late-afternoon light, the glass-and-metal envelope—a combination of curtain walls and corrugated anodized aluminum cladding—takes on a golden hue.

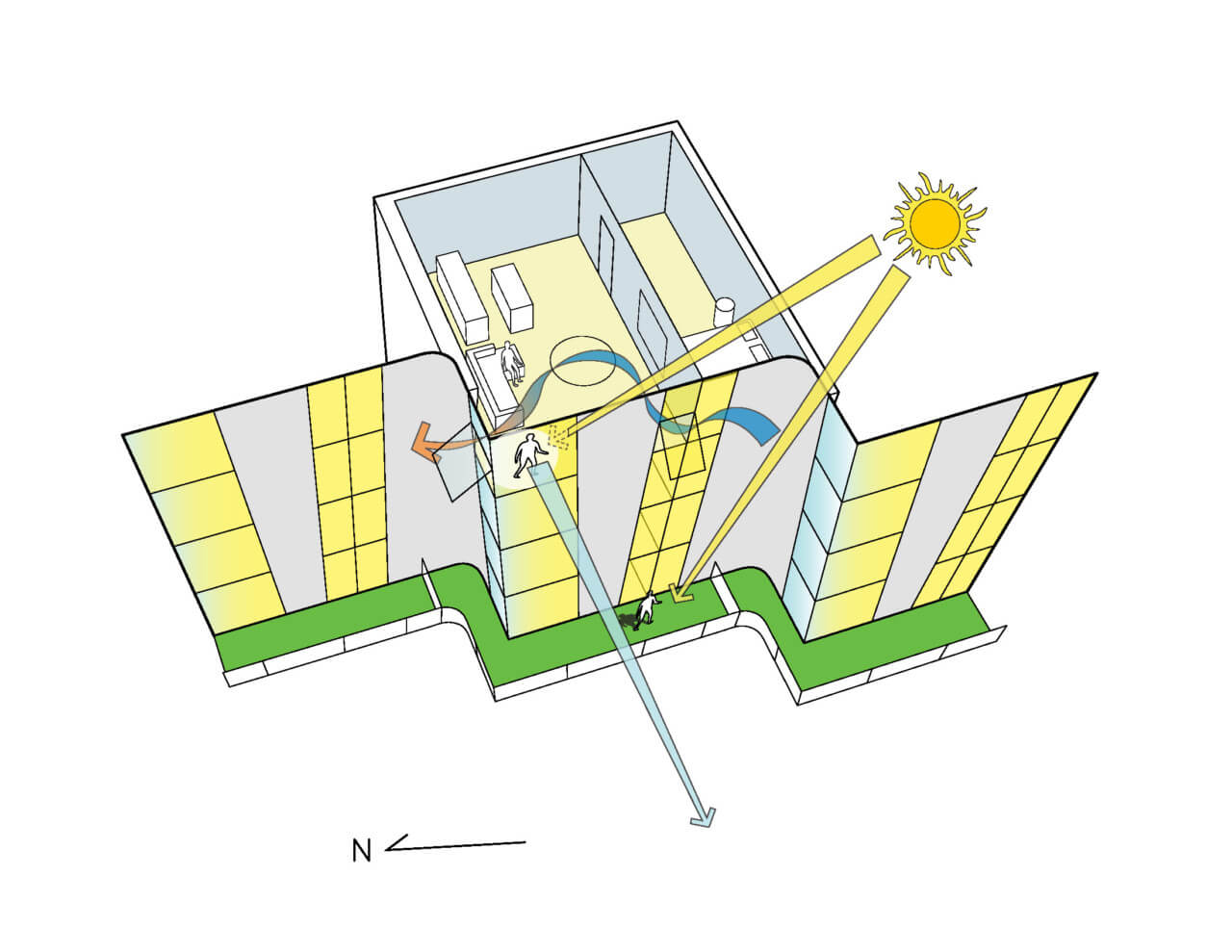

But for all its extroverted tendencies, the tower was conceived “from the inside out,” said Juliane Wolf, a design principal at Studio Gang. She traces the project’s form to the early conceptual design phase, when firm founder Jeanne Gang sketched out the plan of a single unit, rotated on its side. Repeating and mirroring the shape (and leaving space in the middle for an elevator core) resulted in a plan that is reminiscent of an oak leaf—fitting, as One Hundred borders St. Louis’s Forest Park.

With the majority of the 316 condominiums oriented east to west, residents enjoy expansive views of the vast parkland and, looking eastward, the Gateway Arch. The sawtooth slab creates opportunities for wraparound views in every unit. Grouped into four- and five-floor tiers, the floor plates grow incrementally wider as they move up in the building, before snapping back to the narrowest width and repeating the pattern again. The building employs a unique structural system of “wallums”—wall-and-column hybrids whose thickness ranges from 4 to 9½ inches—“to capture the floor plates as they are growing outward,” Wolf said.

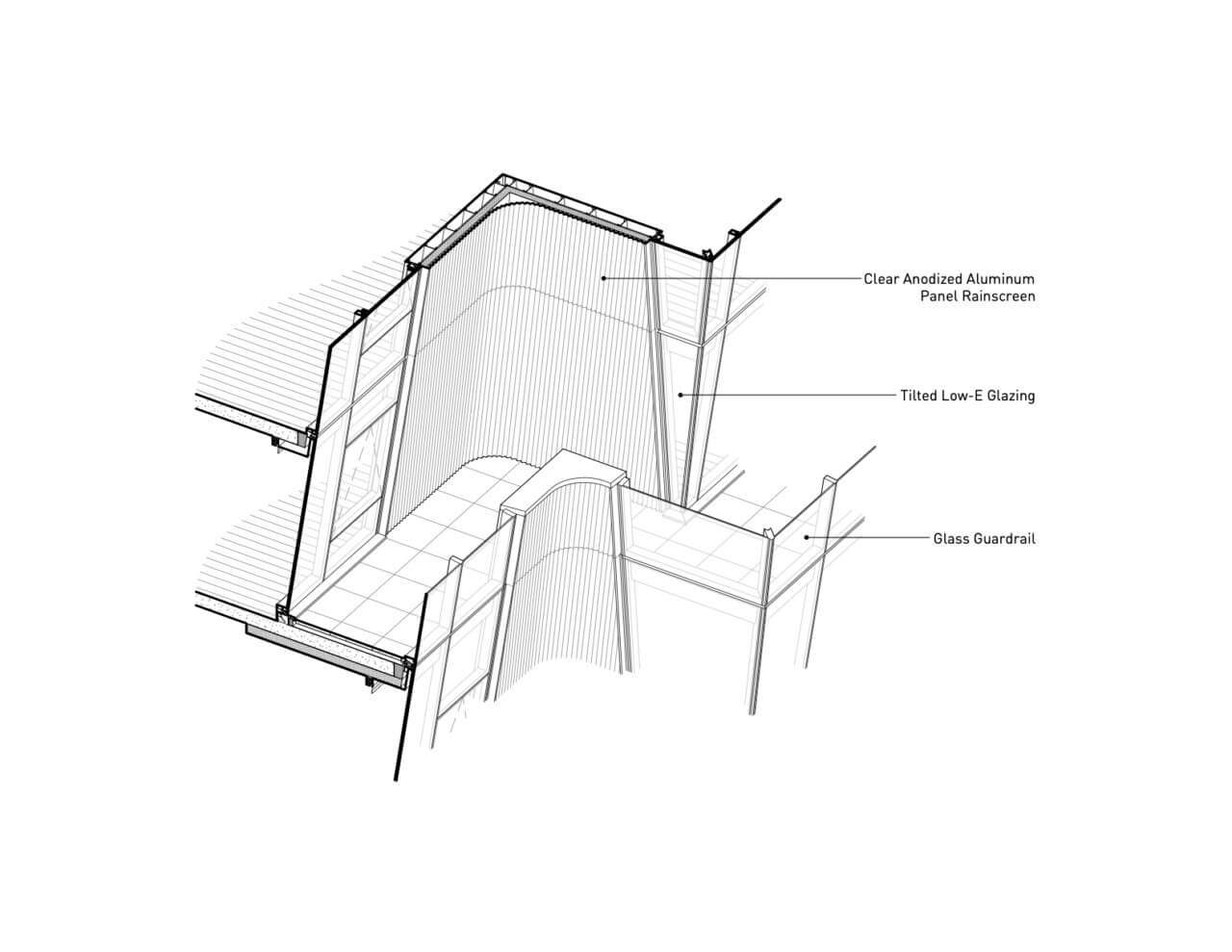

At their longest, the cantilevers span nearly six feet, which becomes the width of the outdoor terraces that terminate the glazed tiers. These mostly private balconies are hemmed in by glass railings and aluminum elements of the facade; consultants Studio NYL ensured thermal breaks in between, so these safety features wouldn’t become hot to the touch during summer. The canted unitized curtain wall system incorporates argon-filled insulated units with a low-e coating and standard elements including operable awning windows and glass doors. The latter required more detailed articulation to ensure geometric compatibility with the wider panel system. “There’s always this dynamism and changing edge-of-floor condition that the angled facade needs to meet,” said Christopher O’Hara of Studio NYL. “That was the biggest challenge of the project.”

The sharp diamond edges of the glass tiers are complemented by the curved bands of anodized aluminum. (The same aluminum was used to fabricate the Z-purlins that clad the tower podium.) Wolf chose the metal because of the way it “changes throughout the day [and] picks up the color of the sky,” she said. The ability to reflect light expressively, demonstrated daily by the Gateway Arch’s sunset winks and shimmers, may yet give St. Louisans outside One Hundred’s confines something to look back at.